There are few strategic natural resources as important as gas, gold or oil, but there is one that is less known and that is decisive in practically any industry and therefore, also in geopolitics: the rare earthwhich are neither earths nor rare (in fact, they are a list of 17 metals). The state that has enough rare earths in its territory and the capacity to extract them will have much to gain to become a power. Well, if you can cough China, the absolute leader in rare earths so much in reserves as in production.

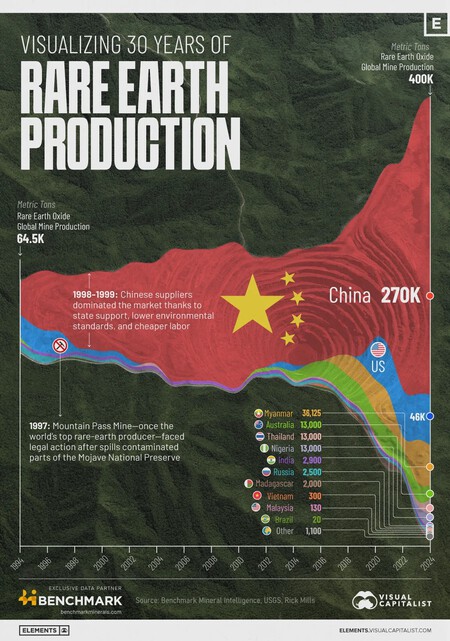

A picture is worth a thousand words. But today the power of China is discussed is one thing and another if the Asian giant started by winning the game. Spoiler: no. The United States Geological Survey It has a very complete database where to visualize production by country from 1994 to the present (among other information), but more than a table, it is better seen with images. Thus, at a glance you can see its beastly hegemony in this chart from Visual Capitalist from 1994 to 2024.

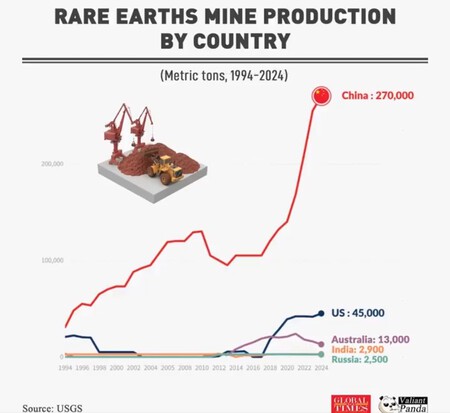

An animation still counts more. The Visual Capitalist illustration shows Chinese superiority, but the evolution of rare earth production by country is better seen with an animation showing its meteoric rise because yes, the global rare earth industry has been profoundly transformed in the last 30 years.

In just three decades, China has gone from having a 47% quota to almost 70% of the 400,000 metric tons produced today (by the end of 2024). Or what is the same, going from manufacturing 31,000 metric tons to 270,000 metric tons, something that can be seen in this animation by Global Times and Valiant Panda:

How America Lost Control. It’s worth stopping the animation at the beginning, because in the 90s the United States was the world’s largest producer of rare earths and Mountain Pass was its main plant for obtaining them. Its average extraction was around 20,000 – 22,000 tons. And then, in 1997, came the Mountain Pass environmental disaster: a burst pipe in the eponymous mine that contaminated the Movaje Desert with toxic radioactive waste.

Between the disaster and the subsequent lawsuits, production suddenly fell to 5,000 tons between 1998 and 2002. It would then fall to 0 in the 2000s. It would be in the 2010s when it began to recover: now the United States is around 46,000 metric tons. As Rocío Jurado sang, now it’s too late, lady: it was also in the 90s when China went into steamroller mode.

The unstoppable rise of China. That China has come to dominate world production hides several keys. The first, the ability of its suppliers to offer lower prices Thanks to state aid, laxer environmental standards and cheaper labor made possible costs that the West could not cope with.

China had the resources, but its victory came because it was able to build an entire industry while the rest of the world watched. Producing the raw mineral is only the first step, then it must be separated to achieve a high degree of purity (between 95 and 99%, depending on the application) in a complex, expensive hydrometallurgical process that, as we have seen, leaves radioactive waste along the way.

Where it still dominates more: refining. Because although China has a share of almost 70% of world production, its dominance is even more overwhelming in refining: it produces around 90% of world refining. In fact, other countries such as Australia or the United States extract minerals, they turn to China for refining. If there is no refining industry at the level of extraction, there is no sovereignty.

Other faces. Trump wants to step on the accelerator of national mining and expedite permits, the EU also seeks its strategic sovereignty with laws such as the Critical Raw Materials law and its application in places like Per Geijer’s Swedish megamine. We have already talked about Australia, which at least until this year It will depend on China for refining those 16,000 metric tons that have been around in recent years, but there are other countries that have joined the race.

But while the Global Times animation focuses on great powers, the Visual Capitalist graph reveals new players in the industry such as Myanmar, Thailand or Nigeria, especially focused on more scarce and valuable elements. However, their supply chains are unstable and have their own regulatory and geopolitical risks.

In Xataka | The world’s rare earth reserves, laid out in this graph showing the brutal dominance of a single country

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings