What the hell is the bone of an elephant that lived more than 2,000 years ago doing in a Córdoba site surrounded by ammunition for catapults and arrows like those used in the scorpions? The question arises, but it is what a team of researchers who have just signed have been guessing for years. a fascinating article in one of the most reputable archaeological magazines in the world.

In it they slip that this mysterious proboscis bone unearthed by pure chance in Andalusia could be neither more nor less than the first test direct from the war elephants employed by the Carthaginian general Aníbal Barca.

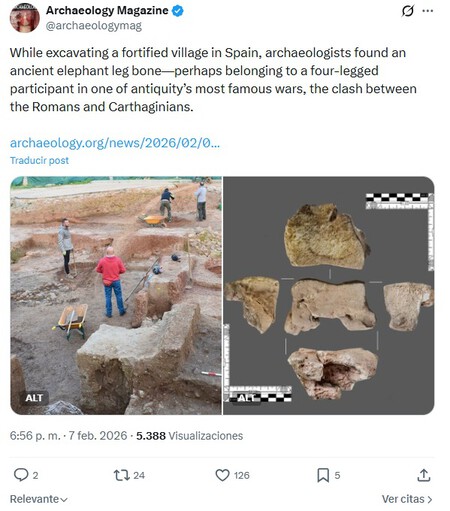

What is this bone? A question similar to that must have been asked. towards 2019 archaeologists who, during a emergency excavation to expand the Provincial Hospital of Córdoba, they found a peculiar bone fragment. The piece was not larger than a baseball (measures between 15 and 8 cm), preserved its porosity and peeked out from under what looked like a ruined adobe wall from the 3rd century BC, which probably facilitated its preservation.

That archaeologists unearth a bone during a tasting (even a millennia old one) has little to offer. In this case, however, the fragment held several surprises. The first, its age: 2,250 years. The second (and this is where things get interesting) is its origin: the bone is neither more nor less than the carpal bone of an elephant, something like part of the ‘wrist’ of a proboscide that for some mysterious reason ended up in the Iberian Peninsula.

“He has enormous interest.” The discovery was so exciting, opening up such promising scenarios, that in 2023 it already generated interest outside the academic circuit. In September of that year Rafael Martínez, professor of Prehistory at the University of Córdoba recognized to The Country the expectation around the bone.

“It is of enormous interest given the practical absence of remains of elephants from a pre-Roman context in Europe, excluding ivory objects that were subject to trade and import,” he said enthusiastically. “In any case, this discreet bone can be interpreted as proof of the presence of these animals in the area of current Córdoba between the 4th and 2nd centuries BC”

By then the professor went one step further and ventured a fascinating hypothesis: “It could belong to the period of the Public Wars. It could be the first elephant discovered by Hannibal’s troops, but it cannot be certain.” There were still many questions on the table. For example, its chronology: it was estimated that the animal died between the end of the IV and I BC, a long period that left several possibilities open. Did the bone belong to a Punic elephant or was it more correct to frame it in times of Julius Caesar?

Hunting for answers. The bone may be small, but scientists have not had an easy time analyzing it. To begin with, it has been difficult to specify its species. After a detailed examination they concluded that it must be a large specimen, larger than female Asian elephants. Specifically, they think of a Loxodonta pharaoensis (the Carthaginian elephant) an African subspecies extinct in Roman times. Maybe the name doesn’t tell you much, but they are animals. used by Hannibal for his passage through the Alps.

The other great unknown. Once the species was clarified (more or less), another unknown remained: its antiquity. The bone was a challenge because it did not contain enough collagen and had not fossilized. That did not prevent a study from ending up revealing that the fragment dates from between end of the 4th and beginning of the 3rd BC Live Science It even goes further and precise that the extract in which the fragment was found (part of a fortified Iberian town known as oppida) can be dated approximately 2,250 years ago, at the beginning of the 3rd BC

It is a key fact because it takes us back to a time before the founding of the Roman Cordoba and the turbulent times of Second Punic War (218-201 BC), when Carthage and Rome struggled to dominate the Mediterranean world.

Are there more clues? Yes. And they are just as interesting. Not only was the bone found at the site, protected by a demolished adobe wall. Archaeologists also discovered more than a dozen of bolaños, small projectiles that were used with catapults, and part of what appears to be a spear. They are clues that help complete the story and help to better understand the site, such as recognize researchers in Journal of Archaeological Science Reports.

“The level of destruction fits well within an emerging pattern of events associated with the Second Punic War, some of which are attested in literary sources and some of which are not, spanning both siege warfare and open battlefield contexts,” they explain in statements to Phys.

Why is it important? Because of the implications it has. In your article Martínez and the rest of his colleagues recall that the discovery seems “intimately linked to the events of the Second Punic War in Hispania” and slips a key idea: “This may represent the first known anatomical element of an elephant used by the Punic troops in this war in Europe.”

If they are correct, we would be looking at a first-class find: the bone of one of the elephants of Hannibal’s troops in the Second Punic War.

Is it so relevant? “It could be a historical milestone. There is no direct archaeological evidence of the use of these animals,” clarify Martinez to Live Science. The march led by Hannibal through Western Europe in his attack on Rome and the use of elephants as “war machines” during the Punic Wars it is a very popular episode, but direct and palpable evidence is not abundant.

The episode of passage through the Alps We know it thanks to historians like Polybius or Titus Livy, but the strongest archaeological evidence today is traces. That could change now, although for now the Córdoba discovery continues to raise some questions. How did the elephant die? Did he die during a battle in the town? What happened to the rest of the skeleton?

One possibility contemplated by the authors is that the small bone was preserved as a ‘memory‘ or even a trophy that was transported from another place, although is questionable due to the low symbolic value of the piece.

Image | Wikipedia

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings