Saving data “forever” is one of those ideas that sounds simple until you look closely at the media we use every day. A file can be perfect today and become unreadable in a few years, or decades, due to degradation of the material or, directly, because the support ends up failing over time. Therefore, when we talk about preserving information for centuries, CDs, DVDs, hard drives or tapes are not a definitive answer. And it is precisely in that gap, that of a support capable of resisting without permanent care, where projects like Microsoft’s try to open a different path.

Project Silica. This is where this Microsoft Research project comes into play, aimed at rethinking what it means to archive information in the very long term. Instead of relying on conventional magnetic or optical technologies, the system uses ultrafast lasers to modify internal properties of the glass and store data in the form of three-dimensional voxels, which can then be read using optical techniques assisted by machine learning, as detailed by Microsoft in a study recently published in the journal Nature. It does not seek to compete with SSDs or hard drives in speed, but rather to offer a material base specifically designed for long-lasting conservation.

looking back. The Redmond giant has been working on this line for years, and one of its best-known demonstrations came in 2019, when he managed to save the movie ‘Superman’ complete on a glass shard about the size of a coaster. That test confirmed that three-dimensional storage within the material was not just theoretical and that, in addition, the support could withstand heat and water, and even demagnetization tests. What changes now is not the fundamental idea, but the degree of technological development that could bring it closer to real preservation uses.

From the laboratory to common glass. The central novelty of the 2026 announcement is not only in the estimated longevity, but in the material used to achieve it. Previous research relied on high-purity fused silica, which was limited in cost and production, while the new study demonstrates the possibility of encoding information in borosilicate glass, a widely available and much cheaper material. According to Microsoft, this advancement directly addresses marketing hurdles related to the storage medium. Now, this does not mean that the technology is ready to be deployed, but it does reduce the distance between scientific experiment and real application.

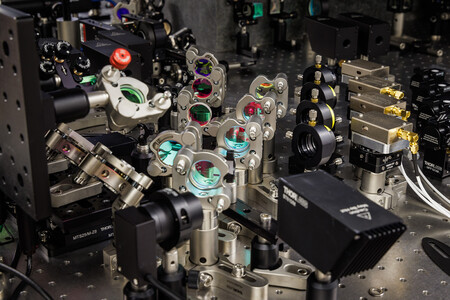

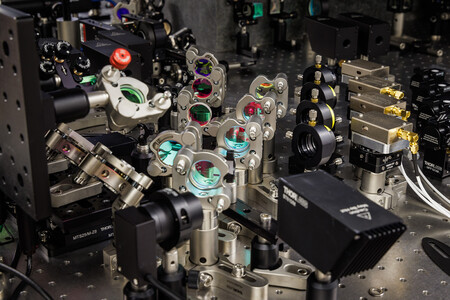

Simpler and faster writing. The work released this week introduces relevant changes in the way data is written and read. The team has introduced so-called phase voxels, which can be formed with a single pulse, and has refined the writing of the birefringent voxels to reduce pulses and speed up the process, including a “pseudo-single-pulse writing” approach. Added to this are parallel writing techniques to record multiple data points simultaneously and a simplified reader that now requires a single camera, with machine learning support for classification and interference mitigation.

Detail of writing equipment during data coding with high speed multibeam laser pulses

The figures. Technically, the system can reach densities of up to 1.59 gigabits per cubic millimeter, which translates to about 4.84 terabytes in around 300 layers inside a glass chip that is 12 square centimeters square and 2 millimeters thick. That capacity is roughly equivalent to millions of printed books or thousands of 4K movies. Of course, this is a capacity that does not go unnoticed. As we can see, rather than competing in speed, the interest is in how much can be preserved in a small space for extremely long periods.

10,000 years. The estimates come from accelerated aging tests in which etched glass plates are subjected to high temperatures to simulate the passage of time, a common methodology in materials science. The results of tests carried out by the research team suggest that information could remain readable for periods of more than 10,000 years under normal storage conditions, a longevity tremendously greater than that of current electronic media. Even so, these are projections based on experimental models, not direct verification on a historical scale.

What’s next. We are facing a surprising technical advance, but the technology continues to depend on expensive equipment and writing speeds well below current commercial solutions, factors that determine its viability outside the laboratory. Added to this are challenges of large-scale production, future compatibility and adoption models in institutions that really need to preserve data for centuries. For now, Microsoft places Project Silica in the field of shared research, open to other actors developing specific applications.

Images | Microsoft

In Xataka | The first hard drives in history were gigantic. Then a miracle happened: miniaturization

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings