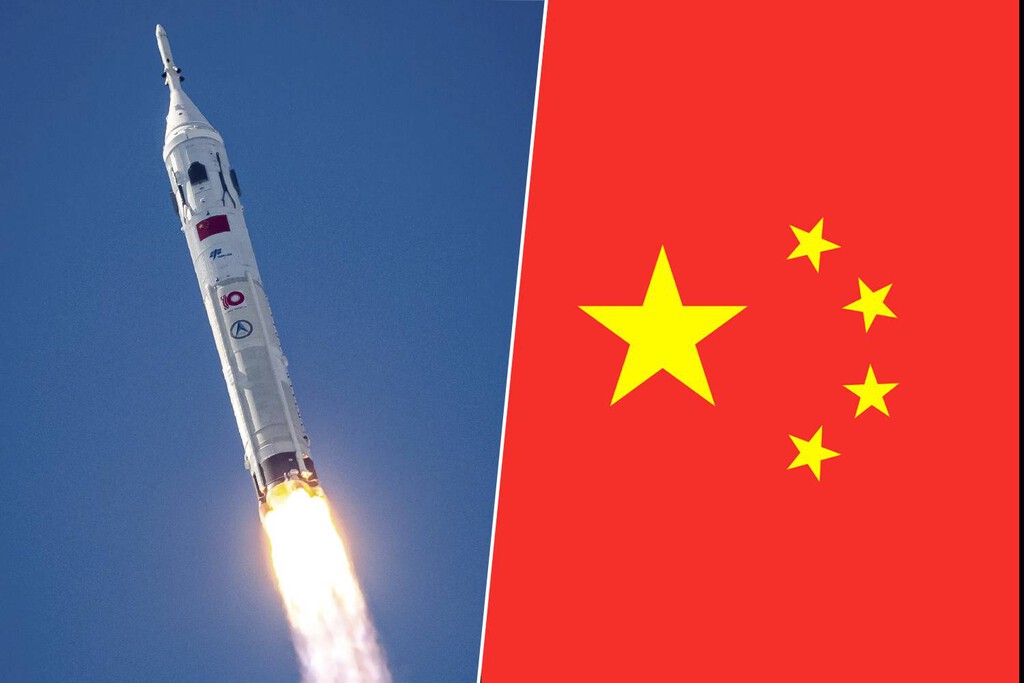

The race for the human return to the Moon has officially entered a new operational phase with China successfully executing the first “lit” flight of its heavy rocket new generation: Long March-10 (LM-10). A test that has not only validated its propulsion capacity, but also certifies the safety of its future crew in the most hostile launch environment.

Where. This milestone, achieved since Wenchang launch pad (Hainan), places the Chinese lunar program on a firm and technically verified trajectory to meet its strategic objective: putting humans on the lunar surface before 2030.

The litmus test. The essay recently made marks a turning point, since, unlike the tests static or scale models from previous yearsthis has been a real flight with ignition. The LM-10 took off in a prototype configuration with the goal of achieving the maximum dynamic pressure (Max-Q).

In aerospace engineering, Max-Q is the critical moment during the climb where the aerodynamic forces on the vehicle structure are most violent. It is the “worst scenario” possible for an emergency that could threaten the safety of the crew, and it is precisely at that moment that the abort command was sent to the Mengzhou manned ship (the successor of the Shenzhou).

There are differences. What distinguishes this essay from those carried out by other historical powers is the sophistication of the subsequent sequence. At first, the Mengzhou capsuleseparated from the rocket and activated its escape enginesmoving away from the “danger zone” at high speed, validating its ability to save the crew in extreme aerodynamic conditions.

On the other hand, as the capsule descended toward a controlled splashdown, the first stage of the LM-10 rocket was not jettisoned. For the first time in a test of these characteristics in China, the stage continued its ascent briefly and then executed a controlled descent and landed in the sea.

A success. This success simultaneously validates the structural integrity under maximum stress, the compatibility of the interfaces between rocket and ship, and the partial reusability of the system, a technological advance that brings China closer to the operational efficiency of companies such as SpaceX with Artemis. All this within a context where China and the United States ‘fight’ to see who is the first to return to the Moon.

A change of concept. Wenchang’s success is just the tip of the spear of a much more complex system known as the CMSA’s “Earth-Space Transportation System for Manned Lunar Flights.” This architecture moves away from the “one giant shot” concept and opts for a two-launch and orbital rendezvous scheme.

The three pillars. The first of them is the Long March-10a colossus approximately 92 meters high capable of placing about 70 tons in low Earth orbit and about 27 tons in lunar transfer orbit. The most interesting thing is that its modular design and the recovery capacity of the first stage are fundamental for the economic sustainability of the program, since the entire structure is recovered for subsequent tests and missions.

The second pillar is Mengzhouwhich is designed for deep space missions and is larger and more capable than the current Shenzhou. Its development, which began conceptually around 2017-2018, has culminated in a modular vehicle capable of supporting atmospheric reentry at lunar return speeds. The third is a dedicated lunar landing module known as Lanyue waiting in lunar orbit.

{“videoId”:”x96edv6″,”autoplay”:false,”title”:”China’s space suit to go to the Moon”, “tag”:”China”, “duration”:”64″}

Roadmap. This includes two separate launches of the LM-10: one to transport the Lanyue module and another for the crew on Mengzhou. The final objective is that both vehicles will perform a meeting maneuver and docking in lunar orbit before the taikonauts descend to the surface.

Chronology of ambition. The path towards this 2026 flight has been methodical, characterized by a strategy of “short but quick steps” that began in 2013 with the first discussions and the development of prototypes. It was in 2020 when an 8-day orbital test flight was made using a Long March-5B and that validated the capsule’s heat shield and recovery systems.

Finally, it was this month of February when the flight occurred with an abortion in Max-Q and recovery of the stage. If we look to the future, before the end of 2026, “zero altitude” abandonment tests and complete tests of the Lanyue lunar landing module are expected, all aimed at meeting the 2030 launch window.

A duel of titans. The comparison between the United States and China is practically mandatory in these cases. While the United States relies on the raw power of the SLS Block 1a 98-meter and disposable colossus, China is committed to operational efficiency with the Long March-10. And although the Chinese rocket is a little less powerful, its design incorporates a reusable first stage, which reduces costs and is closer to the sustainability model that SpaceX has popularized in the West, contrasting with the immense expense per launch of the American system.

On the other hand, NASA has opted for a hybrid and complex scheme: it launches the crew in the Orion capsule with the government SLS rocket, and then docks in lunar orbit with the Starship HLSa commercial lander from SpaceX. In contrast, China has chosen a more pragmatic “distributed architecture”: it will carry out two separate launches of the LM-10, one for the Lanyue lunar landing module and another for the crew on the Mengzhou spacecraft, which will meet directly in lunar orbit.

On their calendars. The US program, depending on multiple commercial suppliers and disruptive technologies (such as Starship’s in-orbit refueling), faces highly complex logistics that have accumulated delays for the Artemis III mission. In contrast, China’s centralized and vertical model maintains a firm and predictable roadmap to the year 2030.

In this way, we are seeing two titanic powers with two different philosophies that aspire to be the first to put their astronauts on the soil of the Moon. The great mystery is in all the problems that may arise, as NASA is already suffering with Artemis and that could have altered future plans for its space mission.

Images | China Manned Space Agency

In Xataka | There are satellites in space that need to be “towed.” And a company from Galicia has exactly what is needed

(function() { window._JS_MODULES = window._JS_MODULES || {}; var headElement = document.getElementsByTagName(‘head’)(0); if (_JS_MODULES.instagram) { var instagramScript = document.createElement(‘script’); instagramScript.src=”https://platform.instagram.com/en_US/embeds.js”; instagramScript.async = true; instagramScript.defer = true; headElement.appendChild(instagramScript);

was originally published in

Xataka

by

José A. Lizana

.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings