When on Monday, October 20, Pedro Sánchez advertisement that “the Government of Spain will propose to the EU to end the seasonal time change”, he did not suspect that he was about to reopen a much more arcane and unmanageable debate: that of Galicia and its time zone.

And the Galicians are good when the subject is brought up to them.

A historical claim. Internet is full of examples of this proverbial Galician anger. As they say, until 1940, Galicia (and, by extension, peninsular Spain) was in the zone of the United Kingdom and Portugal. It was a “temporary” measure that became permanent.

And the consequences are more noticeable in Galicia because due to its geographical position it has very late sunrises in winter and extremely late sunsets in summer.

“A scientific aberration.” In what we have been doing for centuries, the Galician Nationalist Bloc has promoted again and again the proposal of place Galicia in the same zone as Portugal. What’s more, in 2016, all the Galician parties asked that Spain returned to Greenwich zone. Without much success, really. And, despite the fact that it has been defended and studied a lot, the national response It’s been a permanent no.

Because? Let’s go in parts, because this has a nutshell: during the Second World War, practically all of the countries of Western Europe changed time zone. In some cases, it was because of the invasion of Nazi Germany, yes; In others, it was a (more or less) voluntary decision by the different countries. Be that as it may, one after the other, they all switched to Berlin time.

However, that is not what is striking. After all, in war situations, exceptional measures are taken. What is really striking is that, after the War, none of those countries returned to their previous zone. Not just Franco’s Spain, no: everyone.

And the explanation, although it may not seem like it, is much more solid than it seems.

But let’s talk about time zones… When in 1912 is celebrated the ‘Conférence internationale de l’heure radiotélégraphique’ and the 24 time zone system was approved, the lecturers turned to a very specific (and very useful) astronomical phenomenon: the fact that noon is stable throughout the year.

That is, noon occurs almost every exact twenty-four hours and, therefore, establishing the time of each place in the world (adopting the time zone) turned out to be something really simple and revolutionary. Satisfied, they returned to their countries aware that they were making history.

The whys were very clear… Although the First World War meant that the international time convention was not ratified by its members until 1919, everyone seemed convinced. After Versaillesthe different countries began to progressively unify their schedules. It didn’t really affect us. Spain was on the Greenwich meridian since January 1, 1901, like most European countries, under the Meridian conference of 1884. But there were many countries that did have to make important changes.

After all, having a different schedule for each city (as was the case until then) made everything much more complex than necessary. “Normalizing” and “standardizing” the time was a key element for the desired ‘boom’ in rail transport, airships and incipient aviation: coordination costs were beginning to be unaffordable.

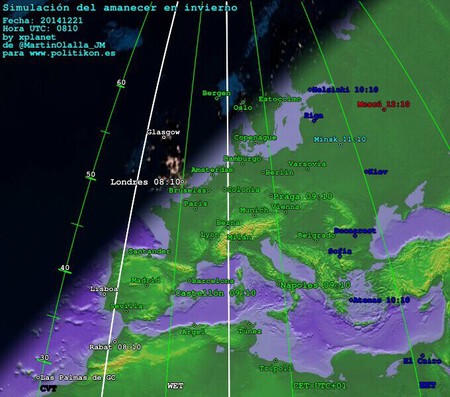

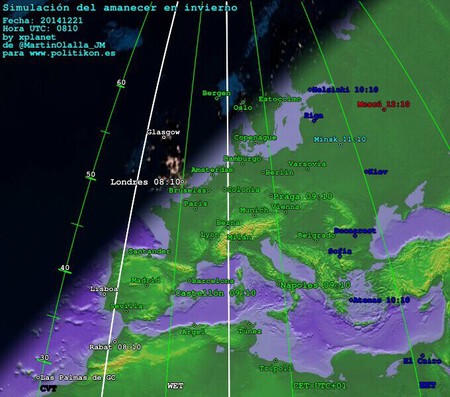

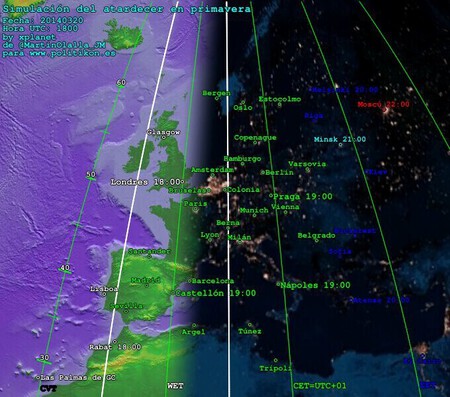

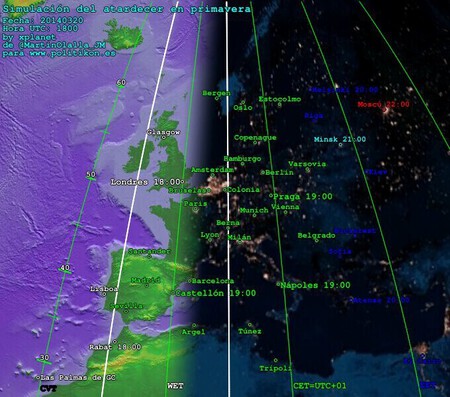

Martin Olalla

Martin Olalla

…but people had other ideas. Despite rationalist optimism, the greatest experts knew that none of this was a magic solution. In 1844, the “father of spindles” Sandford Fleming had already said that,

“The adoption of correct principles of time reckoning will not change or seriously alter the habits to which they are accustomed. They will not lose anything of value. The Sun will rise and set and regulate all social usages. (…) People will get up and go to bed, start and stop working, have breakfast or dinner at the same current time intervals, and our social habits and customs will not change.”

And, indeed, people continued doing their thing. The problem is that this “his” consisted of something strange: suddenly, we began to realize that societies did not establish their schedules around noon, but around dawn.

The most curious thing that almost all the countries in Europe discovered when changing to the Berlin time zone is that, in reality, what they were doing was adapting the civil time to the one that citizens actually had. That’s why no one went back to the old spindle: because it works better.

Martin Olalla

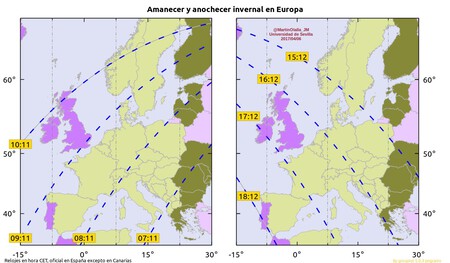

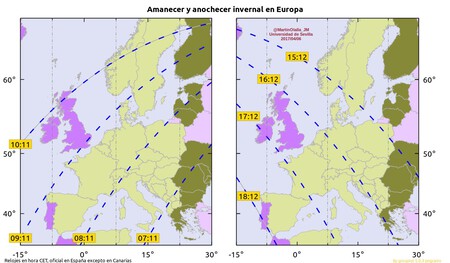

How does it work better? The best way to summarize it is with a phrase: “in winter, when it is daytime in Ourense, in Madrid, or in Barcelona; it is not daytime in London.” In fact, it is even daytime in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. This does not depend on the time zone, it depends on the fact that the sun illuminates the spherical surface of the Earth.

Does it work better for all of Spain? During autumn and winter, yes. Without any doubt. In spring and summer, things are not so clear. During these seasons, the sun hits much less obliquely and this means that the sunset fits much better with the time zones.

The result is that the imbalance that we carry causes nightfall in Galicia much later than would be “normal” or desirable.

This is a real problem, of course. But since the central issue is the variability with which the sun affects these areas, it is also not clear that introducing an extra time zone for Galicia (in the portuguese way) or for the Balearic Islands (as has also been claimed) will solve all the problems. I would trade one problem for another — let’s remember that Portugal has been one of the countries least open to eliminating the time change.

But in addition, it would generate many coordination problems and very few comparative advantages.

Image | MrMingsz (Wikimedia Commons)

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings