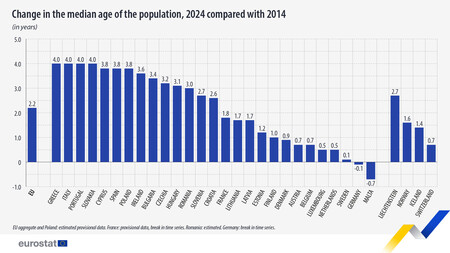

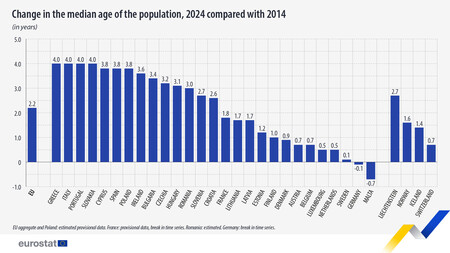

In June the latest Eurostat data putting the EU median age at 44.7 years (and growing). The reading then seemed more or less clear. Europe’s demographic collapse was bringing it closer to an invisible threshold that was once unthinkable: the Middle Ages. 50 years old.

Half a year later, the data has not improved.

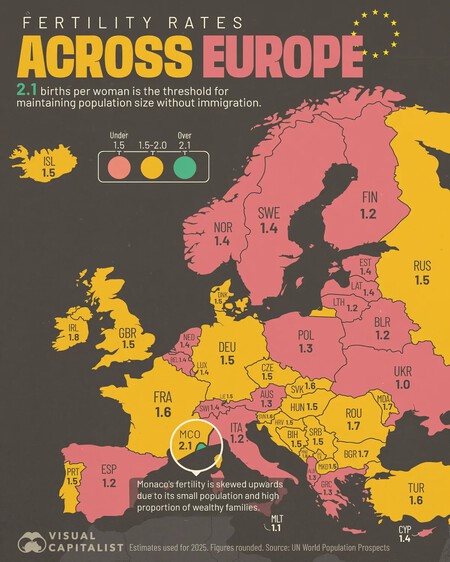

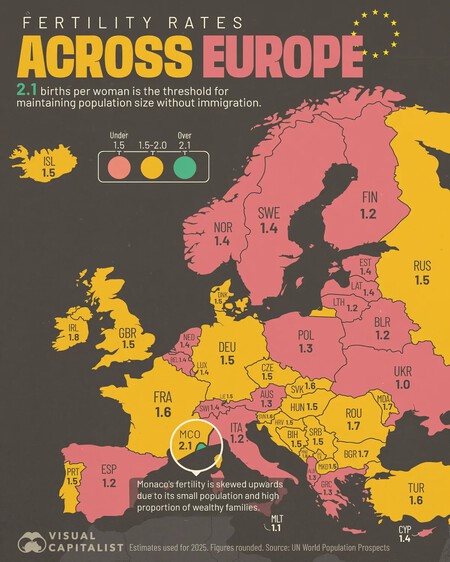

Historical contraction. Yes, Europe is heading towards a demographic turning point unprecedented since the black plague from the 14th century. After decades of sustained decline in birth rates, the population of the European Union will reach its maximum next year and it will start after a prolonged fallthe first of its kind in centuries.

This is not a temporary adjustment, but rather a deep structural change that threatens to redefine the economy, the welfare state and the social balance of the continent. The alarm does not arise only from the total number of inhabitants, but from the aging speed and the thinning of the working-age population, on which the pension, health and care systems built over generations rest.

Political panic and a race. counted the Washington Post that, given this panorama, governments of all ideological stripes have entered into a race against time to see if a combination of economic incentives, public policies and cultural messages can reverse (or at least stop) the decline in birth rates. In the Nordic countries, for decades exhibited as a model of conciliation and well-being, commissions of experts have been created to understand why their systems did not prevent the collapse of fertility.

In France, the discourse has acquired a almost military tonewith calls for “demographic rearmament” after a drop of 18% in births in just ten years. In the east and south of the continent, especially in countries governed by nationalist forces, the response has been more direct: money, tax advantages and an explicit exaltation of the traditional family as a pillar of the nation.

Incentives and results. Italy offers bonuses to working mothers with two or more children. Poland has increased notably the monthly transfers per child and has expanded tax breaks for large families. On paper, these policies seem compelling, even enviable from countries like the United States, where the cost of raising children is systematically cited as the main brake to birth.

However, the European experience shows a repeated pattern: even the most ambitious programs barely succeed in slowing the decline, don’t invest it. The problem is not the lack of public effort, but the magnitude of the phenomenon they face.

Hungary, the laboratory. No country better embodies the ambitions and limits of this strategy than Hungary. For more than a decade, the government has deployed a support system of a generosity comparable to that of Scandinavia, allocating around 5% of its GDP to family policies, a higher proportion than the United States dedicates to defense.

The range of measures it’s wide: leave for grandparents, subsidized mortgages for young married couples, loans of up to $30,000 that become subsidies if the family has three or more children, and lifetime tax exemptions for women with three children, extended to mothers of two children under 40 starting next year. The message is clear: having children is not only desirable, it is a matter of national survival.

Initial successes. They remembered in the post that for a time, the data seemed to prove this bet right. Hungary’s fertility rate went from one of the lowest levels in Europe to figures that suggested a sustained recovery. But the relief was short-lived. In recent years, the trend has been reversed and the country has practically returned to the European average.

For some demographers, the program did not generate new births, but rather advanced decisions by those who were already planning to have children. Others point out that, although the impact on fertility is limited, the policies have coincided with an increase in marriage, a reduction in child poverty and greater female labor participation. The key question is whether these collateral benefits justify the enormous public spending.

State limits. Beyond the checks and exemptions prosecutors, the decision to have children remains deeply personal and increasingly complex. The rise in housing prices, persistent inflation and job insecurity they weigh as much or more than any incentive.

Added to this is a factor that is rarely recognized in the political debate: many of the drivers of the decline in birth rates are social advances that no one wants to reverse. Widespread access to contraception, decline in teen pregnancy, and increased education and career opportunities for women have transformed motherhood and fatherhood in a late choice, carefully calculated and, for many, expendable.

Modernity as a trap. The fertility drop has spread so widely that many experts interpret it as a consequence inherent to modernity. Parenthood is delayed until one’s thirties, when one has achieved job and economic stability that comes later and later. Social media idealizes a life focused on the individual, travel, and personal freedom.

dating apps multiply apparent options, but they make lasting commitment difficult. And a generation raised in small families has less daily contact with babies and children, fueling overly negative perceptions about the sacrifice involved in raising children.

A politicized debate. Not everyone considers the population decline to be a tragedy. Some defend assuming it as a gradual transition towards more sustainable societies, questioning apocalyptic visions who talk about “demographic collapse.” In the long term, even in the most pessimistic scenarios, Europe would still have hundreds of millions of inhabitants.

But these global figures hide a much more immediate structural problem: the imbalance between workers and retirees. In just a few decades, the ratio of people of working age to each elderly person will increase. will have drastically reducedputting under strain systems designed for a demographic pyramid that no longer exists.

The fragility of immigration. For years, immigration has been presented as Europe’s demographic lifeline. However, this option is becomes more uncertain as fertility falls across almost the entire planet. Even countries that until now were large demographic reserves show pronounced declines.

In this context, analysts believe that immigration can buy time, but it will hardly solve a problem that is globalizing. Furthermore, the debate has been contaminated by cultural wars, with discourses that mix demographics, identity and values, further polarizing any attempt at consensus.

The great challenge. Europe thus faces a dilemma without easy answers. Financial incentives can move a few tenths in the statistics, and those tenths matter in the long term, but they are not enough to reverse a trend linked to profound transformations of society. He aging It is not just a question of numbers, but of expectations, values and trust in the future.

As long as that trust continues to erode, any demographic policy, no matter how ambitious, will continue to collide with an invisible limit but forceful: the perception that bringing children into the world it’s a risk too big on a continent that is no longer sure where it is going.

Image | pickpik, Vladimir Yaitsky, Visual Capitalist

In Xataka | The demographic debacle in Europe, exposed on this map with a deceptive guest: Monaco

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings