In the late 1970s, the idea that a nuclear reactor could fall from space ceased to be science fiction and became a real problem on the table of several governments. A Soviet satellite with a reactor on board It had lost control and was heading towards the Earth’s atmosphere, without anyone being able to specify where its remains would end up or what consequences the impact would have. In the midst of the Cold War, secrecy and urgency marked decisions. From there, questions arose that remain uncomfortable today: what was a nuclear reactor doing in orbit, why that risk was accepted, and what happens when technology escapes the script.

As CBC points outOn January 24, 1978, the Soviet satellite Kosmos-954 re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere after weeks of tracking by American radars. No one knew with certainty where he would fall or in what state his remains would reach the ground. Eventually, fragments of the device were scattered over a vast region of northern Canada, from the Northwest Territories to areas that are now part of Nunavut and northern Alberta and Saskatchewan. What began as an orbital control problem suddenly became an international emergency with scientific, diplomatic and health implications.

The day the Cold War left radioactive remains over Canada

Kosmos-954 was neither a scientific satellite nor an isolated experimental mission, but one more piece of a Soviet military system designed to monitor the oceans. It was part of the US-A series, designed to locate large ships, especially American aircraft carriers, using radar. To power this system, which is very demanding in terms of energy consumption, the Soviet Union resorted to a compact nuclear reactor, a solution that allowed operate for long periods without depending on solar panels. That technical choice explains why the satellite had fissile material on board and why its loss generated so much concern.

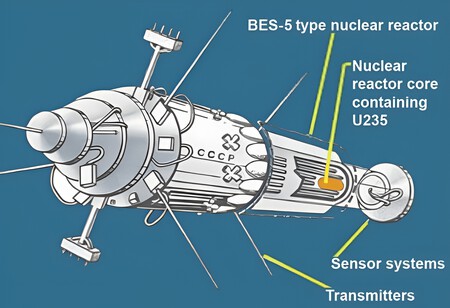

The technological heart of Kosmos-954 was a BES-5 reactor, known as “Buk”, developed specifically for Soviet military satellites. This type of reactor used uranium-235 and was designed to power the US-A system radar for the life of the satellite. The BBC estimates that 31 devices were launched with BES-5 for this family of satellites, and places the use of reactors in space until the end of the 1980s, with launches that continued until 1988. That history was not a clean line, according to the BBC: there were previous failures and accidents, including serious problems in one of the first flights in 1970 and the fall of another reactor into the Pacific Ocean after a launcher failure in 1973, in addition to the plan security plan contemplated moving the core into a waste orbit to prevent its return to Earth.

Arctic Operational Histories explains that The signs that something was wrong came weeks before re-entry. Tracking systems detected that Kosmos-954 was progressively losing altitude, an anomaly that indicated a serious failure in its orbital control. The United States began to follow its trajectory with special attentionaware that the satellite had a nuclear reactor on board. The big unknown was not only when it would fall, but whether the Soviet security system would manage to separate the core and send it to a safe orbit before the device entered the atmosphere.

When it was confirmed that the debris had fallen on Canadian territory, the problem took on a completely new dimension. Authorities knew the fragments were scattered over a vast, largely remote, snow-covered region, making any quick assessment difficult. The first measurements detected radiation in some points, although without a clear map of the contamination. Faced with this uncertainty, Canada had to quickly decide how to protect the population and how to locate potentially hazardous materials in an extreme environment.

To confront an unprecedented situation, Canada turned to international cooperation. Operation Morning Light mobilized Canadian and American military personnel, scientists and technicians, many of them from units specialized in nuclear emergencies. From improvised bases in the north, flights equipped with sensors capable of detecting radiation from the air were organized. Each anomalous signal led to more detailed inspections, in a race against time marked by extreme cold and lack of infrastructure.

As the search continued, it became clear that the contamination was more complex than expected. Not only visible fragments of the satellite appeared, but also much smaller radioactive particles, difficult to detect and remove. This forced the teams to take extreme precautions expand tracking areas. At the same time, delicate communication work began with the northern communities, who wanted to know what real risks existed for health, water and the fauna on which they depended.

As the weeks passed, the operation narrowed its objectives. The official Morning Light phase lasted 84 days, although CBC describes the search effort as extending through most of 1978 and the search covering an area of 124,000 square kilometers. In this process, 66 kilograms of remains were recovered and Canada considered the immediate threat to the population and the environment contained. The economic cost was raised and Ottawa claimed 6.1 million dollars from the Soviet Union, which in 1981 agreed to pay half, opening an unusual diplomatic process for an incident of this type.

The case of Kosmos-954 was not closed with the removal of the remains from the ground. In the months since, the incident reached international forums and fueled an uncomfortable debate about the use of nuclear power in space. Several countries demanded greater security guarantees and more transparency in programs that, until then, had been developed under strong secrecy. The episode served to reinforce the idea that space accidents do not understand borders and that their consequences could directly affect third countries.

Images | Arctic Operational Histories

In Xataka | Mars is left with one less line of coverage: NASA loses contact with its key orbital repeater

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings