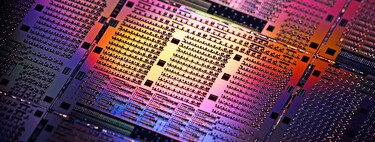

A mysterious American startup called Substrate has made its appearance with a purpose extraordinarily ambitious: compete head to head with ASML. The Dutch company has become the master of the segment of advanced photolithography machines for chip manufacturing, but at Substrate they believe they have the key to turn the tables.

Why is it important. ASML has no competition in the market since it placed its first equipment of UVE photolithography. The ASML thing is a monopoly de facto: If a chip manufacturer or designer wants to access to produce the most advanced models, it depends entirely on the Dutch company. No one has managed to stop it since then, and even China, which is trying to free itself from that dependence, it’s really complicated.

Substrate. This is the name of this startup that has developed a new team in which use particle acceleration to manage lithography. This technology allows microscopic circuits to be etched onto silicon wafers, and this new company claims that its machines could be in manufacturing plants in the US within the next two years. It all sounds very good. Maybe too much, but they already have funds to try: they have just raised 100 million dollars and among investors There is Peter Thielco-founder of PayPal and current CEO of Palantir.

And already, they will try to help create the new TSMC. The challenge is enormous: ASML has invested decades and billions of dollars to perfect its photolithographic equipment, and the complexity of this market makes it very difficult for companies created from scratch to compete. Substrate’s objective is twofold, because it also aims to ensure that its machines enable the affordable chip manufacturing in the US. Or what is the same: it not only wants to compete directly with ASML, but also allow American manufacturers to compete with TSMC on American soil. There it is nothing.

Light is everything. When creating those circuits, some of the lines created are so fine that their dimensions are even thinner than the wavelength of light. To solve that ASML problem they do use of extreme ultraviolet light (EUV) through a very complex set of lenses and mirrors. These machines generate a type of artificial light that is capable of engraving those very fine lines on advanced chips.

Very special X-rays. In Substrate they propose a different idea. Although they do not give all the details to prevent someone from copying them, their machines use X-ray lithography (LRX). A particle accelerator creates a light source from x-rays with a shorter wavelength, allowing the beam to be used to create advanced chips. Current Substrate machines are currently capable of working with 12 nanometer nodes, comparable to ASML High NA EUV machines: That would put them on par with the most advanced chip production lines in the world.

LRX technology is not new. This technique has existed since the 1970s, but had been abandoned because longer wave techniques (UVP and UVE) continued to scale without the need to overcome the great technical challenges of RXL. In substrate they seem to have precisely the solution to those problems, which focused on optics and the need to use massive particle accelerators as a light source.

And they promise brutal cost savings. At Substrate they maintain that their LRX equipment will have an estimated cost of about 40 million dollars, compared to 400 million for ASML’s High-NA EUV. In addition, there would be another associated revolution: the possibility of carrying out the so-called single exposure patterning at advanced resolutions (2 nm, 1 nm and beyond), thus eliminating the additional costs of the multipatterning (multiple exposures). If that promise is fulfilled, the production cost of advanced wafers would be 50% lower according to Substrate.

But. Of course, it’s one thing to say it and another to do it. The precision of the process, they explain in Semianalysisis a monumental obstacle. The transfer of patterns (going “from light to silicon” almost “carving it”) remains problematic, and among the challenges is solving the roughness of the edges of the printed patterns, which is amplified during engraving.

There is also the problem of stochastic noise (shot noise, random fluctuations in photons that cause defects) and secondary electron blurring inherent to the high energy of X-rays, which fundamentally limits resolution. There are also currently problems with the 1.6 nm overlay, which is still high for more advanced processes where 1.0 or 1.2 nm are sought.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings