Finding gold, diamonds or oil has been the origin of many of the greatest fortunes in history. A stroke of luck or investing in excavations in the right area and at the right time were the key to amassing an enormous fortune.

However, sometimes that fortune comes with much less “glamorous” finds. In the United Kingdom at the beginning of the 19th century, coming across the remains of a dinosaur was very striking. But encounter his feces could become a lucrative business made many millionaires lucky.

There’s a new gold: dinosaur dung

At the beginning of the 19th century, the famous fossil hunter Mary Anning He came across some strange dark and irregularly shaped nodules on the coast of Dorset, a county in the south of England. The paleontologist studied these strange fossilized remains and discovered that they were full of fish scales and small fragmented bones trapped in their structure. That intrigued experts who began studying them in more detail.

In 1829, the geologist William Buckland examined them and determined that these remains were fossilized feces of ichthyosaurs and called them coprolites, kopros (dung in Greek) and lithos (stone). These fossils from the Lower Cretaceous (110 million years ago) were preserved in soft, phosphate-rich seabeds. As the writer Martin Sayers highlighted in an article in History Extraalthough they looked like common rocks, their high mineral content triggered a unexpected “gold rush” to find them.

in 1845 John Stevens Henslowa Cambridge professor, revealed that these curious fossils not only had a paleontological interestbut they also contained up to 40% phosphoric acid that they had absorbed from the clay soil, and it was perfect for compost after grinding it and treating it with sulfuric acid.

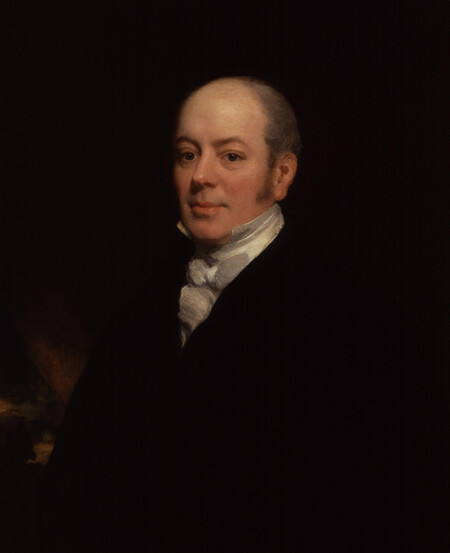

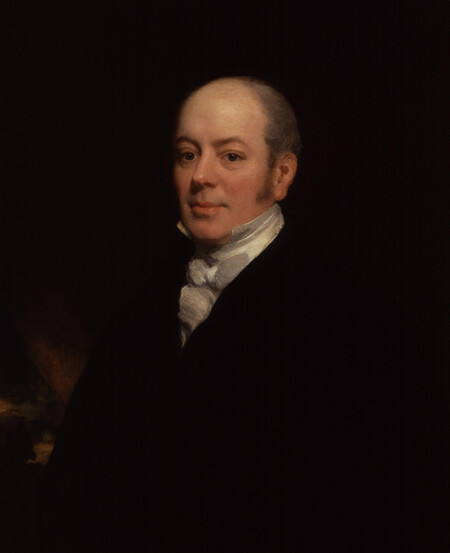

William Buckland analyzed coprolites

After the Napoleonic Wars, the United Kingdom, like the rest of Europe, suffered a pressing shortage of food, so the fertilizer use that increased crop productivity skyrocketed.

In this context, finding raw materials to manufacture these fertilizers became a lucrative business. That is where the depositions that the dinosaurs were dispersing throughout what is now southwestern England come into play.

Coprolite fever

According to Sayers’ account, in 1858, Robert Walton leased land in Cambridge for £200 per acre per year, which was in itself a small fortune. His intention was to create one of the first open air mines to extract in an industrialized way the numerous coprolites that had been found in the area. The starting signal was given for a business that made many seekers millionaires.

Coprolite mine in Trumpington (Cambridge)

According the studies At St Mary’s Twickenham University in London, thousands of miners flocked to the area and deep shafts were dug to extract the coveted dinosaur droppings. With its extraction not only did the businessman earn a lot of money, he also paid very juicy salaries. A miner earned 10 shillings a day washing and sorting coprolites, twice as much as a farmer.

This caused all agricultural activity in the area to become mining, industrializing the southern part of the United Kingdom. The demand for labor was such that workers and coprolite seekers began to arrive from all corners of the country, making the “coprolite fever“.

Fossilized dinosaur poop fetched £3 a ton, and a mine like the one Walton had created produced around 300 tonnes of coprolite. That is to say, if you had enough money to pay the rent for the land and the labor, the profitability of the extraction could make you earn a lot of money. This unleashed madness in Cambridgeshire, Suffolk and Bedfordshire.

From 1850, local and foreign miners flooded the county, excavating areas of southern England like burwellReach or Coldham’s Common with simple methods: dig holes 6 to 10 meters deep and scoop out clay with buckets or carts to filter its contents and find the valuable coprolites.

According to the historical recordslocal production reached 90% of British phosphate, some 54,000 tons annually in 1877, valued at more than £150,000 a year. The data points Because, in 1874, the dinosaur dung industry contributed around 628,000 pounds annually to the British economy, exceeding by more than 20,000 pounds the contribution made by materials such as tin, which in those years was a key product in United Kingdom exports.

The risk of extraction was very high because the clay terrain made the excavations prone to collapses, burying the workers, and diseases from contaminated water plagued the camps of coprolite seekers.

Even so, the fever lasted decades and was revived during World War I, driven by demand for phosphorus to make ammunition for the army. However, once declared the armistice in 1918the coprolite mines in the United Kingdom were sealed again and all the product was imported from the US, where the coprolites were closer to the surface and their extraction was much simpler and cheaper.

Image | Unsplash (David Valentine), Wikimedia Commons (United States Geological Survey, Diego Delso, National Portrait Gallery), Cambridgeshire Collections

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings