In my years of training as a journalist I remember how they told us to study the radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds. My Radio and Television Information teacher told us that it was an exemplary event that could help us in the future practice of the profession to evaluate the responsibility of the media and to understand the mechanisms by which the so-called “fourth estate” could influence the social reality we serve.

What perhaps the teachers who transmitted that information to me did not think is that they were right in what they had told me, but for a twofold and partially wrong reason.

The legend of War of the Worlds

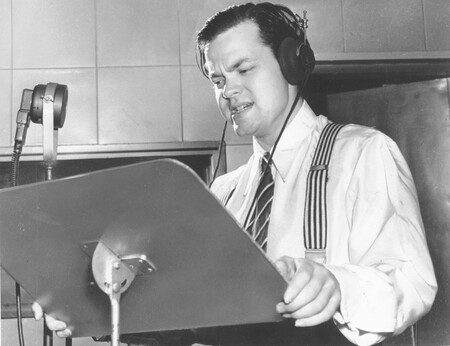

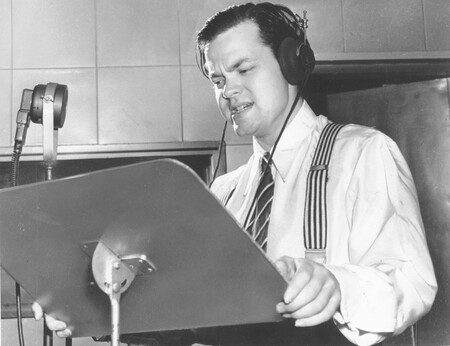

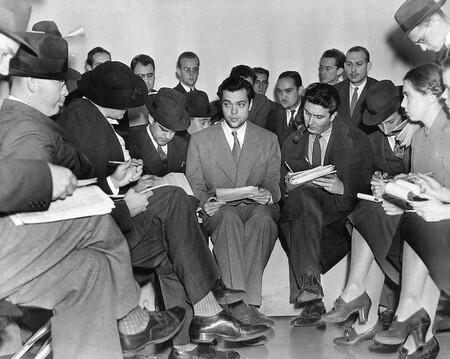

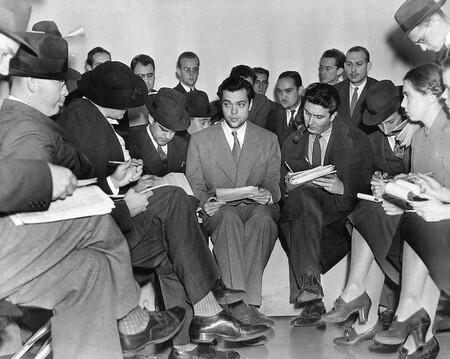

The story is well known: HG Wells, a widely known science fiction writer at the time, had a story titled The War of the Worldsthrough which aliens would come to Earth to conquer humanity. A beginner but ambitious young man named Orson Welles decided to adapt the script to the radio format, giving it a newsreel structure for his television program. Mercury Theater on the Air on CBS and that he would read with other colleagues on the night of October 30, 1938, on Halloween Eve.

The broadcast, the reading of this work, lasted an hour in which the aura of truthfulness was maintained except in three momentsone at the very beginning, another 40 minutes into the recording and another at 55. They indicated that it was a dramatization. For the rest, the fiction of that Martian invasion that was taking place in Grovers Mill, New Jersey, remained live.

The myth, the documentaries and reports about the case and the journalism classes I attended said that Welles, the hired actors and the sound montages were so believable (and the audiences so naive) that within minutes of them starting to simulate a supposed alien attack the streets of the country were filled with hysterical and shocked masses. Panic attacks, people stockpiling supplies, collapsed police services and who knows what else. We assume that the people who did not hear those warnings were able to connect to the program after the warning and listened to the program without knowing that it was fake.

And why wouldn’t we think like that? The newspapers of October 31 had carried the story to the foreground: “False war bulletin spreads terror throughout the country”, “Radio play terrifies the nation”, “Radio listeners panic, they confuse a war drama as a real chronicle”. These are some of the headlines that could be read about an event that, as it was said later, caused rivers of ink to flow in the form of more than 12,000 articles in newspapers throughout the United States.

The reality is that, as a series of experts have reflected on different occasions, this interpretation largely falls into the realm of fake news. To support it here we use, above all, the study of professionals and experts from Princeton University, from the work of scholar David Miller in his essay Introduction to Collective Behaviorfrom the book Getting it Wrong by W Joseph Campbellfrom the work of sociologist Robert E. Bartholomew and from what journalists Jefferson Pooley and Michael J. Socolow have collected for Slate.

What events did occur

The broadcast did cause some effects.

We know that some Grover’s Mill locals, believing their town’s water tower had been transformed into a “giant Martian war machine,” fired guns at the water tank. There was at least one woman who sued Welles and his team for causing her a panic attack and one man received direct compensation from the future film director who paid for the shoes that a listener said he had given up to pay for the train ticket he needed to escape the alien catastrophe.

It is also true that calls to hospitals increased from people telling them where they could go to get donate bloodand police stations in the New Jersey area were also called, but most who did this were looking to find out if it was a false alarm. They wanted confirmation that it was a joke, but they also called to protest about this program that could be deceiving people or to congratulate them on that great special on that Night of the Dead. But nothing more.

All of them came together to serve the approach that the written press wanted to give: that the CBS program had caused mass hysteria, that the radio was lying and deceiving its listeners and that they had created a major problem.

And the lies that were published

The rumor that people were being treated for shock in New Jersey hospitals was false, as the Princeton Radio office later revealed. The news that a man had died of a heart attack because of the program, as reported by the Washington Post, was also not true. People didn’t jump out of the windows either. In general, hundreds of articlesmany with supposed witness accounts, witnessed chaos that, in truth, had not been such.

I remembered Some time later in his memoirs Ben Gross, radio director of the New York Daily News, that in truth the streets of New York They were half empty. It would also later be known that CBS had disconnected the Welles broadcast in different local affiliates in the country to show regional bulletins that, they assumed, would interest their audience more than a little play by Martians.

The biggest scandal of all, the audience figures. It was said that more than a million people had listened to the program, when it could not be true. In fact, most people were listening to the NBC rival to ventriloquist Edgar Bergin’s popular radio show. And with most people we are talking about a 2% audience for the NBC show, as demonstrated by an independent survey that was done simultaneously with the broadcast.

There is no doubt that in popular culture the idea that The War of the Worlds was a a before and afterthat the phenomenon must have been so traumatic that both the public and journalists took more care after the event in what to tell and what to believe. But, as we see, the reality is that the story that we all believe happened was actually a fabrication by the traditional press.

We are the ones fooled years later, not the listeners of the 1930s.

A good part of the newspapers, their editors, had reasons to inflame that story. On the one hand, sensationalism is a weapon of seduction, a lure from potential readers. Also reasons to pressure against the radio, a relatively new format (and the first major rival that print journalism has faced) and that had displaced both its clients and its advertisers: income from print advertising had fallen, so criticizing the lack of verisimilitude and the deception that radio produced was a way of granting itself a certain prestige.

And why didn’t Mercury Theater on the Air deny it?

Because it was a myth too beautiful to destroy. No creator as hungry as him would miss this opportunity to wear such a striking badge: the man who deceived a nation for one night. His immediate response was to publicly apologize, but as soon as he saw that his face was on the front page of the newspapers, that he was becoming an internationally known face, surreptitiously helped to fuel the fire of controversy.

The program didn’t go badly either. Thanks to the press, to the bad press, the Mercury Theater gained the attention of the Campbell Soup Companywhich later sponsored them in a new program called The Campbell Playhouse.

As a journalist I can’t stop thinking about the paradoxes of this anecdote. My teachers used this event as a sobering example of what can happen if you lie to your audience, but at the same time that collateral lie, that subsequent exaggeration, has been established in our psyche since then without causing us any problems.

We all like to visualize a bunch of Americans bewildered and alarmed by a threat as unreal as it is laughable just because they heard someone say it on the radio. And other media took advantage of that desire to believe to construct a parallel story that also keeps us in an information fog.

At the same time, here we feel the absence of that originality or evolution that we sometimes give ourselves with respect to past generations. Today it is popular to think that the press is being distorted because of AI and clickbait. We have all read a news story in which journalists attribute a strong and unilateral response to an event that is actually the compilation of a few voices sprinkled with X, distorting the sociological background that we could only extract with a deep analysis of all the data. Today’s headline for the Internet would not have been very different: “A radio program passes off a story as news and social networks catch fire.”

Finally, that uncomfortable feeling of living in a truth supported by a very thin thread. If it were now discovered that the War of the Worlds researchers who have been uncovering the myth of broadcasting have falsified their studies, we would return to square zero.

In Xataka | I asked the AI any nonsense and now I’m writing a news story about it

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings