At the dawn of the new space race, when public agencies and private companies they promise orbital tourismreusable ships and commercial stations, the most uncomfortable reality prevails again: in an environment where everything is calculated to the millimeter, where engineering reaches almost obsessive degrees of perfection, a tiny fragment is still enough to leave a crew without a return vehicle.

The last ones, the chinese.

The invisible fragility. Actually, enough with very littlea screw, a metal splinter, a grain of paint that advances at 28,000 km/h, to leave the astronauts stranded. The recent episode of the Shenzhou-20probably hit by a fragment so small that it could not even be traced, has once again demonstrated that, beyond the marketing of “new space”, the basic vulnerability of manned missions remains intact.

Recent history, since Chinese Tiangong station to the ISS, confirms that extended stays, disabled capsules and improvised returns are not anomalies: they are the inevitable price of operating in an environment saturated with objects traveling at hypersonic speeds and where any unforeseen It triggers complex logistics chains for which no one is fully prepared.

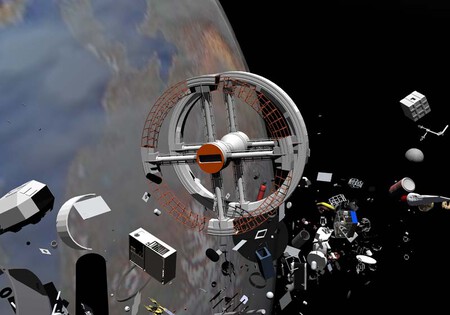

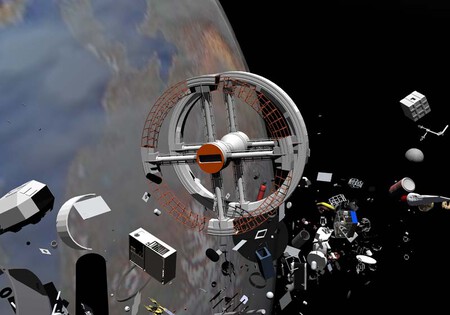

The perfect storm. The exponential increase of activities in low orbit has created an ecosystem where the number of active satellites far exceeds 9,000 and where dozens of thousands of fragments Majors follow the trail, but millions of microremains (the size of a screw or less) evolve without possible detection. The practical consequence is that any capsule, no matter how robust, faces a permanent risk of invisible impacts which can crack windows, damage heat shields or render thrusters useless without warning.

In parallel, the logistical complexity grows: more private actors, more different vehicles, more dependence on the weather and more critical points in each mission. The combination of orbital saturation, increasing use of space stations and increasingly compressed operating cycles widens the margins of error and multiplies the chances of a crew being temporarily left without safe return. It is not a hypothetical scenario: it is already recurring, and affects equally to China, the United States and Russia.

The Shenzhou-20 as a structural symptom. He chinese incident It synthesizes all contemporary problems. A ship ready to bring the taikonauts back it develops tiny cracks in one of its windows. There is no obvious alarm, but the possibility of this damage compromising reentry is enough to declare it useless. The outgoing crew must wait nine more days and end up returning in the newly arrived capsule. This maneuver, in turn, leaves the new crew without an escape vehicle and forces the Chinese agency to launch against the clock. an emergency capsule.

The process works because the system is designed to improvisebut the sequence reveals the absolute dependence of each module and the fragility of losing a single one. The Shenzhou-20 is moored to the station to be returned without crew. Thus, the “centimeter screw” becomes in main actor of a chain of decisions that affects several crews and requires the mobilization of launchers, equipment and additional resources. In the era of megaconstellations and commercial flights, this vulnerability not only persists: is amplified.

History of space “strandings”. He chinese case It is not isolated. In recent years, similar incidents have affected the United States and Russia. Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore nine months passed on the ISS because their Starliner was not safe for reentry after propulsion failures. Frank Rubio stayed a full year in orbit when his Soyuz was pierced by a micrometeoroid and his capsule became unusable. History repeats itself: a critical device is no longer reliable, a contingent improvises, another vehicle arrives and the astronauts return via an alternative route.

Even external factors (weather, a previous accident, a geopolitical conflict) can leave a crew with no immediate return. Since the Soviet collapse caught Sergei Krikalev on Mir until the flight suspensions after the Columbia disasterthe notion of “staying longer” is deeply embedded in agency culture. Astronauts do not perceive it as a failure, but at an operational level it marks constant points of tension that tend to worsen as low orbit becomes more crowded and unpredictable.

Space junk. The most disturbing factor of this new stage is that a growing part of the risk comes from objects that cannot be detected. Current radars track relatively large pieces, but the swarm of microfragments (these from collisions, tiny detachments from aging satellites, metal particles, loose paint, glass, microscopic screws) follow the dynamics described decades ago by the Kessler syndrome: more objects generate more collisions, which in turn multiply the fragments.

These small objects cannot be dodged because they cannot be seen. And yet, they possess enough kinetic energy to puncture a ship or cause imperceptible structural failures that only reveal themselves when a mission is about to return. In such an aggressive environment, the question is no longer whether a capsule will receive a minuscule impact, but when and at what critical point it will occur. The Shenzhou-20 does not inaugurate a trend: confirm that we are already inside it.

Persistent risks. Impacts are not the only cause of prolonged stays: the ships themselves, even the most modern ones, show vulnerabilities inevitable. Reentering the atmosphere involves braking from 28,000 km/h to zero in minutes, a process that requires each component to operate with absolute precision. Thrusters, heat shields, sensors, valves, life support systems and automatic sequences are constantly tested, but physical and thermal stress is not supported margin of error.

The first missions for new vehicles often reveal unexpected glitches, such as It happened with Starliner. In these contexts, the safest measure is always the same: extend stay and wait for an alternative spacecraft, such as the Dragon or a Soyuz, to become available. History itself confirms that this logic works and saves livesbut it also emphasizes that the redundancy that is taken for granted on dry land is much more difficult to reproduce hundreds of kilometers away.

Space tourism and “normality”. Plus: the boom of space tourism enter a disturbing contrast. While agencies accumulate cases of damaged capsules, crews without immediate return and improvised launches to cover emergencies, the commercial discourse presents low orbit as an environment almost domestic. The reality is that risks are increasing, not decreasing, and the threshold for fragility remains the same: an invisible impact can completely change a mission.

The scenario most feared by experts is not a massive failure, but a cluster of small incidents caused by the proliferation of microdebris and increasingly dense orbital traffic. For the occasional passenger on a suborbital flight these nuances are invisible, for a crew that depends on a single reentry vehicle, they determine their vital safety.

The immediate future. The simultaneous expansion of state, private and commercial missions suggests that incidents related to failed returns will be most frequent. As the number of ships, crews and satellites increases, the probability of minor impacts, technical failures and weather-compromised re-entry windows proportionally increases.

Likewise, the vehicle diversification (each with different standards, test cycles and architectures) multiplies the possible points of failure. What happened with Shenzhou-20, Starliner or Soyuz is not specific: they are, possibly, operational previews of what will happen with increasing regularity. The agencies know it and now incorporate these scenarios to their planning: “emergency” capsules, flexible rotations, and supply reserves capable of sustaining crews for additional months.

The great paradox. Thus, at a time when the humanity prepares for lunar bases, private stations and commercial flights as if there were no tomorrow, the most serious threat to the continuity of the missions remains the smallest. It is not the major catastrophic failures that are defining this phase, but imperceptible knocks of objects that cannot be traced, microscopic cracks and specific failures in ships subjected to extreme stress.

Thus, the image of the “centimeter screw” summarizes the paradox: in the era of space tourism and of mega investmentsthe safety of a crew may depend on a particle that no one can see. And as long as orbital traffic continues to grow (until unsuspected limits), that vulnerability will only increase.

In space, the smallest is still the most dangerous.

Image | NASA, CMSA, NASA

In Xataka | China is silent about its astronauts “stranded” in orbit: if the ship is damaged, they have three options

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings