For many dog owners, the your pet’s ability to understand words As ‘ball’, ‘Paseo’ or ‘Chuche’ is a reason for astonishment. But now what dogs can understand a new leap, to move on to compression that goes beyond associating a sound with a specific object. Something that A study Published in Current Biology, it has seen in after its investigation, where they have concluded that dogs can have communication capacities so far reserved for humans.

The investigation. The study has been led by Claudia fleet An exceptional group of dogs known as ‘Gifted Word Learner’.

Some dogs that are not common at all, since they have an extraordinary talent to learn the names of the objects, with vocabularies ranging from 29 to more than 200 words, one, enables that allows them to learn names of objects quickly in playful interactions with their owners.

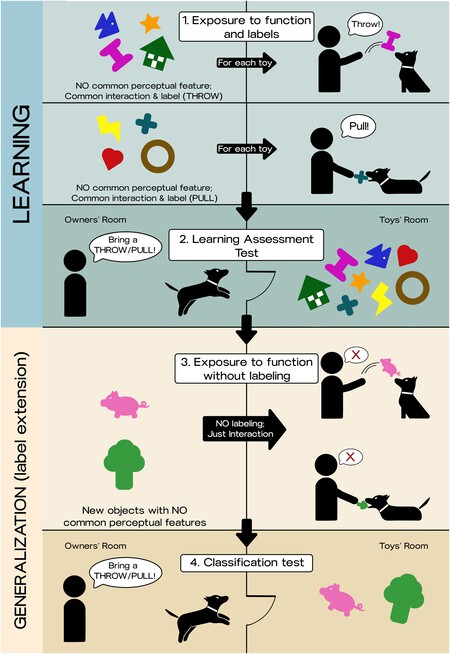

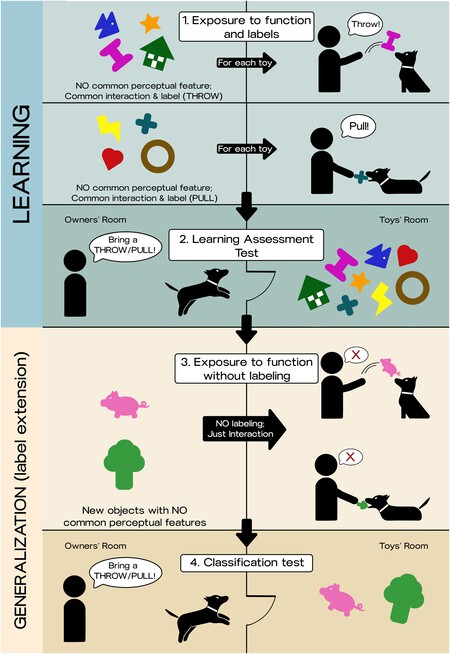

Learning the rules. To find out if dogs can go beyond simple visual recognition, the researchers designed an ingenious four -phase experiment. The first one focuses on dogs learning what they will have to do. To do this, the owners taught their dogs two verbal labels for two toys groups. For example, a set of four objects were assigned the ‘throw’ label and the only interaction was the game of the strip and loosen.

Another set of four toys was given the “launch” label, and with them it was only played to throw them so that the dog would bring them. The crucial thing in this case is that toys within each category did not share any systematic physical characteristic. The only thing in common was the label and the way of playing with them.

The exam. The second phase was to verify if the dogs had come to understand well the rules that had been previously taught. Eight dogs exceeded the test successfully, recovering the right toy with at least 12 of 16 attempts.

New toys. The third phase was undoubtedly fundamental and is the ‘kit’ of the matter. Here the owners introduced completely new toys for dogs and for a week they played with them in the two ways already established above but with a very strict rule: verbal labels of ‘throw’ or ‘launch’ could not be used. The dogs only experienced the role of the toy, without anyone saying their name or for what they were using it.

The fire test. Once all these phases were made, only these new toys were left (with which he had played without appointing it) with other family toys. The owner from another room not to give visual clues asked the dog ‘bring me a’ throw/throw ‘. The dog at that time had to deduce which new toy the owner referred to with this instruction, based solely on the function he had previously experienced with him.

Results. The dogs selected the correct new toy, the one with which they had played in the manner corresponding to the label, with a frequency well above chance. On an average of 48 attempts, the dogs hit 31 times.

This clearly demonstrates that dogs were not limited to learning the names of individual objects. Instead, they created two “mental categories” based on the function of objects: one for ‘throw’ toys and another for ‘launch’. When they met a new and nameless toy, they were able to assign it to the correct category based on the use that was given.

This ability to generalize a label to functionally similar objects, ignoring appearance differences, is a fundamental pillar of language development in children. In fact, this ability emerges in young and preschool children, who learn to understand that both a ceramic cup and a plastic glass belong to the ‘glass’ category because both serve to drink.

The importance. This study is pioneer especially to demonstrate that a non -linguistic species can perform a functional classification linked to the learning of verbal labels, and does so in a naturalistic game context and without having to undergo a lot of repetitions in a laboratory environment.

Until now you could think that dogs worked through perception, but this study comes to change this idea we had. In this case, the fact that animals classify the world mainly by perceptible characteristics such as shape or color is challenged. These dogs were based on the ‘planned utility’ of the object.

In this way, GWL dogs are emerging as an unprecedented animal model to investigate cognition precursors related to language in ecologically valid conditions, offering parallels with child learning.

Open a door. The authors themselves point out that this ability is, for now, exclusive to these “gifted” dogs and should not be generalized to the entire canine population. However, it opens the door to investigate whether this capacity is latent in other dogs and what cognitive mechanisms support it.

Images | Tadeusz Lakota

In Xataka | The most fearsome animals in the world: when nature is much more dangerous than the human being

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings