They cultivated fields, raised livestock, built some of the most amazing buildings on the planet, developed a rich culture that included advanced astronomical knowledge that still intrigue today to the experts. The Mayans are one of the most fascinating civilizations on the planet. And rightly so. Without it it is impossible to tell the history of Central America. However, little by little and as technology allows us to delve into their secrets, we begin to understand something: much of what we thought we knew about the Mayans was wrong.

And that includes its collapse.

What happened to the Mayans? The question is very simple. His answer not so much anymore. As our knowledge of the Mayan civilization has expanded (thanks to resources such as LiDAR technology) has also mutated the idea that historians had of its decline. I remembered it recently in Guardian Marcus Haraldsson remembering what we know about Tikalone of the largest urban centers of the Mayans, located in what is now Guatemala.

“Sudden and disastrous”? The most recent stele located at the site dates back to the year 869 ADwhich leaves the question of what happened in Tikal from that date on. For a time historians assessed the possibility of a “sudden and disastrous” collapse that marked its fate; But today that explanation seems increasingly distant.

Now experts are leaning towards another option: a broad period of decline of around 200 years during which farmers moved north and south and powerful urban centers were abandoned in favor of settlements such as Chichén Itzá, Uxmal or Mayapán, towards the north of the Yucatán Peninsula. There is even talk of the period Classic Terminalwhich goes from the years 750 to 1050.

Changing perspective. This perspective has been adapted over the decades and goes beyond the period of decline of the Mayan civilization.

“We are no longer really talking about collapse, but about decline, transformation and reorganization of society, as well as a continuity of culture,” comment to Guardian Kenneth E. Seligson, associate professor of archeology at California State University (CSU). “There have been several similar changes in places like Rome. (But) we rarely talk about the great Roman collapse anymore because they re-emerged in various forms, just like the Mayans.”

But… What happened? What exactly happened for many of the main Mayan settlements (not all) to begin to collapse towards the 9th and 10th centuries It remains a complex and highly discussed topic. Today the authors point out a combination of factors including changes in trade routes, adverse weather, severe and prolonged droughts and wars, among others. The truth is that in the middle of 2026, researchers continue collecting clues that helps us clear up unknowns about that period.

The importance of water. You don’t have to go far back to read new discoveries that tell us precisely about the collapse of the Mayan civilization. Last August a group of scientists published a article in which they basically emphasized the “important role” that “prolonged droughts” played in the Mayan decline. For their study, the researchers analyzed a stalagmite located in a cave in the Yucatan, a true geological and archaeological treasure if its oxygen isotopes are analyzed.

The examination revealed a series of periods of severe drought between 871 and 1021, during the Terminal Classic, stages marked by water shortages during which the Mayans found it “extremely difficult” to grow their crops.

It may seem exaggerated, but the study revealed eight droughts during the rainy season that lasted at least three years. Not only that. The longest drought lasted about 13 years. Other previous studies, carried out from sediments collected in the Chichankanab lagoon or stalactites rescued in Belizehad already suggested the role that climate played in the Mayan collapse.

Question of droughts (and something else). Months after that study, in November, Benjamin Gwinneth, from the Université de Montréal (UdeM), published another that helps complete the ‘photo’. The Canadian institution recalls that between 750 and 900 AD the population of the Mayan lowlands suffered “a significant demographic and political decline” that coincided with “episodes of intense drought.”

What Gwinneth’s work questions is whether this collapse is explained only by the lack of water. Curiously, their research is also based on the analysis of sediment samples dating back to around 3,300 years ago.

And what exactly did he do? Gwinneth dedicated himself to analyzing samples taken from Laguna Itzán, in present-day Guatemala, near an archaeological site Maya. To be precise, they focused on three “geochemical indicators” that reveal the evolution of fires, vegetation and population density in the area (something they estimate thanks to fecal stanols) for thousands of years.

The first conclusion they obtained is that the first settlements appeared in the area 3,200 years ago and for centuries the Mayans cultivated, burned to clear forests and used the ashes as natural fertilizer. It also gradually increased the population of the area. Over time they even changed their “agricultural strategy”, dispensing with fire.

A “stable” climate. The second conclusion (and this is the interesting part) is that, unlike Mayan populations located further north that did suffer “devastating droughts”, in Itzán the climate was relatively “stable” thanks in part to its geographical location, near the Cordillera. Curiously, that did not free Itzán from the crisis that they suffered in other areas of the Mayan world. The question is obvious: Why? If it kept raining there, what dragged them into the crisis?

“Although there was no drought in the area, the population decreased during the Terminal Classic period. Indicators show a drastic drop, traces of agriculture disappear and the site was abandoned,” Gwinneth points out.which recalls that some archaeologists place the beginning of the Mayan collapse in the Itzán area.

Why is it important? Because it suggests that drought (no matter how stubborn) is not enough on its own to explain the Mayan decline. “The answer lies in the interconnection of Mayan societies,” reflects the expert. “Cities did not exist in isolation. They formed a complex network of commercial ties, political alliances and economic dependence,” apostille the researcher.

Catastrophic “domino effect”. It was not necessary for Itzán to suffer in his meats lands the lack of precipitation. When its neighbors in the central lowlands began to run out of water, it could be unleashed “a cascading crisis”with clashes over resources, collapses of ruling dynasties, mass migrations and the suspension of trade routes…

“Itzán fell into ruin not because of lack of water, but because it was caught in chaos when the system of which it was a part collapsed,” summary from UdeM. A drought was not needed for the general collapse. If this theory is true, the very “interdependence” that existed in Mayan cities unleashed a fatal “domino effect.” Gwinneth’s proposal is interesting because it suggests that, beyond the climate, the collapse was a complex phenomenon influenced by economics and politics.

Searching for the right questions. The most curious thing about Mayan culture is that, despite the fascination it has generated in popular culture for decades, our knowledge about it is still far from complete. In fact, we continue to reach surprising conclusions, such as the one reached in 2025 by a team who has dedicated himself to studying Mayan settlements with LiDAR.

Thanks to aerial laser scanning, scientists came to the conclusion that the Mayan population could have been much (very much) larger than we believed, reaching 9.5 or even 16 million of people spread across areas of what is now Guatemala, southern Mexico and western Belize during the Late Classic era (600-900 AD). The figure far exceeds the calculations that were used a few decades ago, which pointed to just a couple of million inhabitants.

“We were expecting a modest increase in estimates, but seeing a 45% increase was surprising,” the teacher recognizes Francisco Estrada-Beli, one of the team members. This great population density confirms that the Mayan lowlands must have been well structured and organized and raises a suggestive reflection: there are who thinks That the big question is not why the Mayan civilization declined, but how the hell it managed to survive.

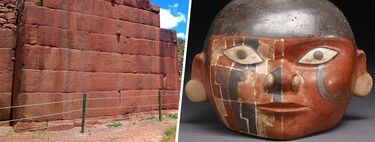

Images | Wikipedia 1 and 2 and Florian Delée (Unsplash)

In Xataka | The Mayan bones that tell a terrifying story: that of ritual violence against prisoners of war

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings