We’ve seen them in movies, novels, documentaries, and museums, but there’s one detail about Roman slaves that’s often overlooked: their demographics. How many lived in the empire? What “weight” did they have? How many were men and how many were women? What was your life expectancy? How the hell did they end up under the orders of the patricians? A Spanish historian has asked himself these questions applied to Hispania and their conclusions They help debunk myths and recalibrate previous estimates. For example, calculate that at least during the High Empireslaves represented 9% of the Hispanic population.

It is just one of his many conclusions.

What has happened? That Fernando Blanco Robles has opened an interesting debate with an article published in the january number from the magazine Lucentum. In it he touches on a topic that is often overlooked when talking about the slaves of Rome: their demographics. To be more precise, Blanco draws a population x-ray of slavery in Roman Hispania.

It’s an interesting approach because, although we’ve spent decades clarifying how they lived, what did they eat or where the serfs whose lives depended directly and literally on their masters came from, there is an equally interesting question much less explored: How many slaves lived in the Empire? And in the Iberian Peninsula?

Why is it important? The researcher himself clarifies it in your article. “It is necessary to deepen the study of demography in Antiquity and particularly as it relates to the Roman era, but it seems equally necessary to include slaves in order to try to demystify demographic assumptions that have been raised.” His is not (far from it) the first work that addresses this issue (complex and thorny), but it does help to clarify certain ideas. After all, not all authors have reached the same conclusions.

If you review the bibliography, you will find authors from the 19th century who calculated that 30% of the population of Roman Italy lived in slavery to others, more modern, who believe that it is more correct to speak of between 15 and 25% of the inhabitants of the Italian peninsula. It is still a very high figure (hundreds of thousands of people), but with a notable difference. That last fork (10-20%) is the same as estimated by some authors for the entire Empire.

What was happening in Hispania? In your article Blanco focuses the focus on a very specific part of the Roman domains: the Iberian Peninsula. What ‘mark’ did slaves and freedmen have in Hispania? What was its demographic weight?

To answer that question (and many others that he addresses throughout his research) the expert relied on data from the Empire and epigraphic sources, ancient inscriptions. Specifically, it identified in the three Hispanic provinces (Baetica, Lusitania and Citerior) 653 private service with 466 registrations. A relevant part of them (230) contained valuable data, such as ages.

With all this information, Blanco has drawn some conclusions. “A population of between 3.5 and 4 million has been calculated for Hispania as a plausible figure. Given the territorial extension of its provinces and the intense economic activity of Baetica and western Citerior, we can assume that in total Hispania reached a percentage of slaves similar to that of Egypt,” details the researcherbefore providing the key figure: in total, in the whole of Hispania the ‘dependent’ population (slaves and freedmen) would represent close to 9%.

Where does that percentage come from? The study takes as reference “the most plausible calculations” drawn up for Italy, Egypt and the rest of the Empire, in addition to a crucial question: the resources necessary for “supply and support.” With all this data, Blanco proposes a simple calculation.

“That would give a slave population of between 200,000 and 400,000, about 300,000-350,000 on average, to which, if we add the number of freedmen which, based on the general provincial average of the Empire, can be calculated at 105,000, it would give us a total of 405,000 dependent population in Hispania.”

That is, freedmen and slaves would represent approximately 9% of the population of Hispania. It is a high figure, but it is far from previous estimates that raised the range above 30%. The article He warns in any case that this is only a “hypothetical calculation” for the high imperial era.

Are there more conclusions? Yes. And although they must also be handled with caution, they are fascinating. For example, the study of Hispanic epigraphy reveals a “clear disproportion” As far as sexes are concerned: if we base ourselves on that source of information, there were many (many) more male slaves than female slaves. They represented 64%. They, only 36%. These are data in line with those achieved in other parts of the Empire, such as Augusta Livia.

And how long did they live? Another very interesting conclusion is the one that tells us about their ages. “The mortality of the group is concentrated in the first three decades of life,” the study points out before qualifying a relevant idea: perhaps the data will shock us in 2026, but they are not far from the general pattern of the Empire.

“The average life expectancy can be established at around 30 years of age. These figures coincide with the same ones that have been studied for the free population (…). In conclusion, nothing indicates to us that their life expectancy and average years of life were lower than the rest of the population. Despite their inferior and dependent legal status, the group manifests the same problems in relation to mortality, fertility rate, children per couple and age of marriage.”

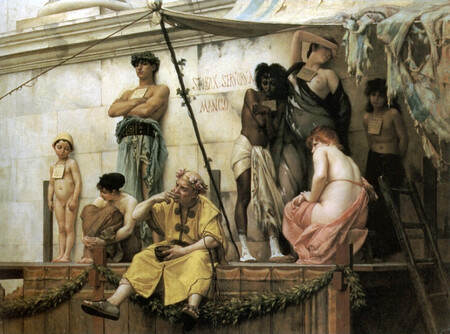

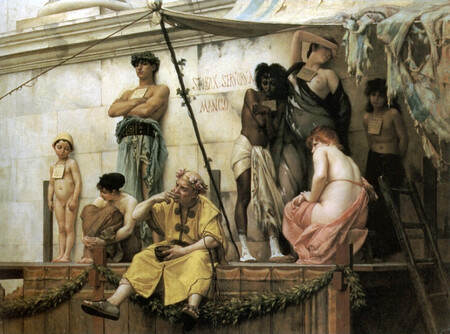

How was he enslaved? Having clarified how many there were and how long they lived, another question remains: How the hell did someone become a slave? Why did he lose his freedom to see himself subjugated and dependent on another person?

There were different scenarios. A person could end up in shackles for being a prisoner of war, through piracy and foreign markets, for being a foundling, or for being a a vernaea slave who is already born and raised in his master’s house. There was even another possibility: “self-selling”, where a citizen sold himself, forced, for example, by the accumulation of debts.

There are authors who believe that among all these sources, perhaps the most stable and that became the main channel for supplying slaves were the vernae. Blanco questions whether this was the case, both throughout the Empire and in Hispania, at least if we trust the epigraphic sources, with only 120 documented cases in Hispania. “The channels of provision were varied and in unequal proportions, depending on the space of the Empire in which we found ourselves.”

Images | Wikipedia

In Xataka | All the amphitheaters built by the Roman Empire, brought together in a stunning interactive map

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings