These are not easy times for the alcohol industry. And not only for the crossfire of the trade war, ups and downs of prices or the apparent loss of interest of Generation Z for drinking. As customers demand less whiskey, cognac and tequila, the giants of the sector have found themselves with a growing stock that some estimates already put at 22 billion dollars. Thousands and thousands of bottles that threaten to strain the finances of large manufacturers and (even worse) unleash a price war that clouds their future.

“The accumulation of inventories is unprecedented,” warn.

A huge “lake of liquor”. So recently described Financial Times the panorama that the large distillate manufacturers have encountered, giants of the sector that have their warehouses full of bottles that cannot be disposed of. To be exact, the newspaper claims that five of the titans of the industry that are listed (Diageo, Pernod Ricard, Campari, Brown Forman and Rémy Cointreau) have a stock of aged spirits valued at 22 billion.

Breaking schemes. If the figure seems high, it is because it is. Those $22 billion mark the highest level of stock in more than a decade and there are already those who warn that they paint a delicate picture. “The accumulation is unprecedented,” recognize FT Trevor Stirling, analyst at Bernstein. The most extreme case would be that of the French cognac manufacturer Rémy Cointreau, which according to the newspaper accumulates aged stocks worth 1.8 billion euros. Almost double its annual income and close to its global market capitalization.

Is there more data? Yes. In recent years the percentage of mature stock over total net sales has increased clearly at Rémy, but also at Brown-Forman, Campari, Diageo and Pernord Ricard. For example, in the case of the British multinational Diageo, this ratio has clearly increased in just a few years: if in the fiscal year of 2022 it represented 34%, it is now 34%. 43%.

The problem is not just the big manufacturers of Scotch whiskey, cognac and tequila. Data from the Tequila Regulatory Council show that at the end of 2023 the Mexican industry had a stock of 525 million liters of that popular distilled beverage. The figure (sum of the product in barrels or pending bottling) is almost equivalent to the country’s annual production. “Much more new liquor is distilled than is sold, and the stock begins to accumulate,” duck Bernstein.

A ticking bomb. The accumulation of stock is not worrying only because of what it suggests to us about the past and current sales pace. It is especially so because of its implications for the future. With more barrels and bottles gathering dust in the warehouses of the big manufacturers there are those who already fear that a price war would break out, a pulse in the market that would aggravate the situation.

For now, FT recalls that there are manufacturers who have chosen to hit the brakes in their factories. This is the case of Diageo, which has production suspended of whiskey in various factories, or from the bourbon producer Jim Bean (Suntory), which has done something similar with its main Kentucky distillery. The problem: often the aged drinks sector works for several years, so pausing its production today can compromise the supply in five years or a decade.

What is the reason? To understand the current stock of the industry, it is necessary to understand several keys. For example, the fluctuations in demand in recent years and the forecasts with which manufacturers have worked. At the beginning of the pandemic, the sector registered an increase of distillate consumption in the US, which led to an increase in production. After the health crisis and with inflation as a backdrop, however, the market returned to normal.

What’s more, the industry had to deal with new challenges that a priori have little to do with its business. The first is the trade war unleashed last year, a scenario in which the alcohol industry was not foreign. In fact, if Jim Bean considered suspending production at his main distillery it was precisely due to the increase in stock and the uncertainty generated by tariffs.

Another key factor is that alcohol consumption (at least of certain types of alcohol) appears to be moderating as more people focus on their physical health and take weight loss medications, such as Wegovy or Ozempic. It is nothing exceptional if you take into account that in 2023 a study Walmart already warned that consumption of Ozempic was reducing food sales.

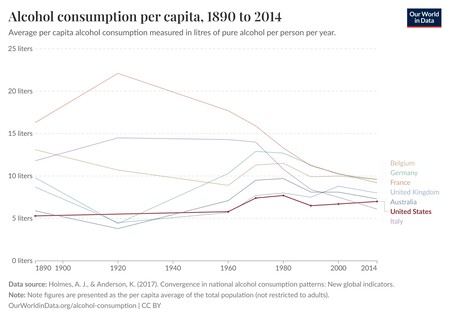

The big question. Beyond these current factors, a key question for the industry hovers: Are we consuming less alcohol in general? Do we drink less than our parents and grandparents? And will the new generations on whom the sector will have to rely on in a couple of decades drink less? There is data that suggests this. The Our World in Data platform has developed a graph on per capita consumption that reflects that almost all the countries analyzed consume less alcohol than a few decades ago.

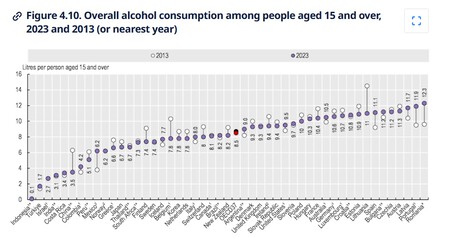

It is not the only study that points in that direction. Another recent one from Gallup confirms that in the US consumption has fallen to its lowest level since at least 1930 and OECD tables They also show that many of their countries (not all) have seen how the intake of liters per person per year decreased between 2013 and 2023. There are those who already warns that the trend does not look like it will stop, fully affecting to the accounts of the distillate industry.

Images | Paolo Bendandi (Unsplash), OECD and Our World in Data

In Xataka | There is an age at which we should stop drinking alcohol forever. Neuroscience is clear why

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings