The world has been looking at the Nordic countries for decades with a mixture of admiration and envy for their model of social welfare. A clear example is Finland, a benchmark in education, aids to motherhood and spent in social benefits. None of this, however, has prevented him from seeing how his birth rate it contracts little by little. In fact, the fall has been so forceful since 2010 and its rate is at such low levels that the Government has decided to hands to work.

Now you have a diagnosis… and a formula with 20 ingredients.

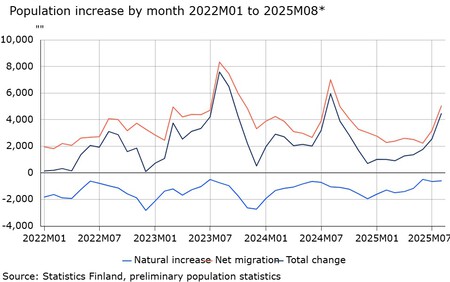

What does the data say? That Finland has a birth problem. A particularly complex one. The statistical basis The World Bank shows that its birth rate has plummeted over the last six decades, going from 2.7 during the baby boom to 1.3 in 2023. The decline was particularly sharp between the 1960s and 1970s, followed an oscillating curve until the last decade and accelerated again towards 2010. latest data of Macrotrends show a slight recovery, but the rate still remains far from past values.

Why is it important? Because it shows that Finland has a problem, one recognized without half measures by the Government itself. “Finland’s birth rate has been declining rapidly over the past 15 years. In 2024 the country’s total fertility rate became as low as 1.25,” recognized last March the Ministry of Social Affairs, which admits that although Finland is not the only country dealing with this challenge, the collapse there has been “exceptionally rapid” in the last decade and a half and threatens to become an economic and social challenge.

“Finland’s rate has fallen to a historic low and the decline has been more pronounced than in the other Nordic countries. There is a considerable gap between the ideal number and the actual average number of children. It is essential to find solutions to reduce the gap,” advocated in spring the Minister of Social Security, Sanni Grahm-Laasonen. In 2023 the indicators of the neighbors Norway and Sweden there were around 1.4 children on average per woman, also far from the replacement rate that allows countries to stay away from immigration.

Why is the birth rate falling? That’s the million dollar question. And the one that the Finnish authorities did a while ago. To answer it in 2024 the Government commissioned a report which had to clarify the factors that hinder the country’s demographic engine and (just as important) explore possible solutions. The task was relevant because, as the Executive assures, in Finland there is “a big difference” between the number of children that couples want to have and those they have.

“Studies show that Finnish family policy has favored both well-being and birth rates and continues to play an important role. However, the current decline is mainly due to the fall in the number of first births and the increase in the proportion of childless people,” reflect Professor Anna Rotkirch, from Väestöliitto (the Finnish Family Federation), one of the experts who participated in the preparation of the birth report.

Did you identify the causes? Yes. And no. The Government quote somebut he also recognizes that there is no “clear reason” that alone explains the decline in birth rates. “Therefore there are no easy solutions to stop it,” the Ministry of Health resigns itself before listing some factors that come into play, such as cultural changes, unstable relationships, health, the situation of the labor market and income or the problems of reconciling professional life and parenting.

The NPR organization was recently one step further and interviewed experts and young Finns to find out how they approached parenthood. Poa Pohjola and Wilhelm Bomberg, aged 38 and 35, are the first ones he cites in his analysis: the couple has been together for about three years and last July they had their first baby, although Pohjola admits that not so long ago he believed he would never have children.

“It seemed impossible to me,” the woman confesses. His case is paradigmatic because it agrees with a phenomenon that Finnish researchers have observed and can be extended to many other countries, including Spain: delayed maternity and the increase in people who directly choose not to have children. In the case of Finland this has led to a fertility rate slightly lower to that of the EU average and nations such as Iceland, Denmark, Sweden or Norway.

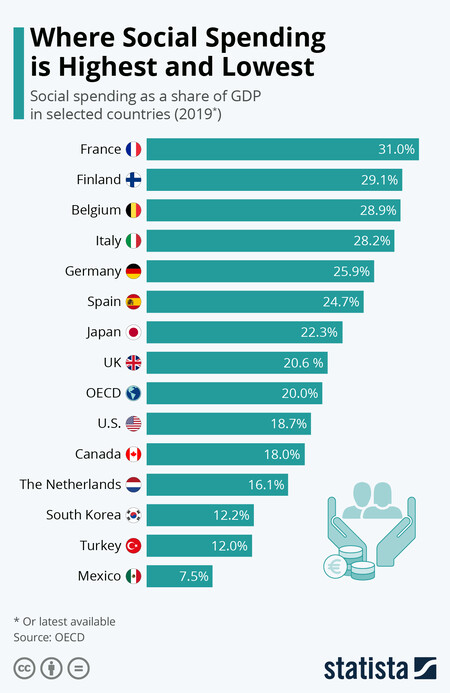

Does it matter beyond Finland? Yes. And it matters because Finland offers a particularly interesting case study. As remember Liisa Siika-ahofrom the working group of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, “in Finland benefits and services for families are relatively good.”

In fact the Nordic countries they usually stand out precisely because of the facilities they provide for having offspring. Specifically Finland does it in aspects such as incentives, education and paid leave. “We can no longer claim that our good family policies explain the good fertility of the Nordic countries,” points out to NPR Annelie Miettinen, from the state agency Kela.

“What baffles researchers is how this can be true, because all of these countries are relatively good at offering family support,” Miettinen said, “but there are really no good explanations for today’s very low fertility rates.” Just as it happens in Spain if the country is managing to weather the demographic storm is basically thanks to the immigration flow.

How to solve it? A few months ago the Government made public a report on the topic that includes twenty proposals focused on the family and birth rate, all based on the premise that the commitment to early childhood education, family leave and economic support will boost birth rates. Until it is confirmed, the Health Department itself remains cautious.

“In Finland the benefits and services for families are relatively good. This means that there are no areas where simple changes can be made,” takes on Sikka-aho. “However, all systems require maintenance and that is what many of our proposals address. It is unlikely that a single measure can increase birth rates. That does not mean we should not try.”

What do the 20 proposals say? Basically they advocate for greater “social dialogue” to find out what the younger population, between 20 and 29 years old, expects, desires and thinks. A key issue if one takes into account that experts relate the drop in birth rates more to “changes in values, lifestyles and relationships” than to changes in social policies or at the workplace level.

Another of its main measures is to provide a “financial incentive” to women who have their first child before turning 30, which can include everything from mortgages to student loans, tax advantages or pensions.

Are there more measures? Yes, some more. Based on the data they manage, the experts propose raising the educational level (a direct relationship is seen between academic training and parenthood), facilitating work-life balance and less dependence on temporary contracts, providing advice and guidance on fertility, improving sexual and reproductive health services or looking after the couples themselves to avoid breakups. He Government has already announced its intention to increase compensation for egg donations.

Images | Vladislav Vedenskii (Unsplash), Jennifer Kalenberg (Unsplash), Statista and Statistics Finland

In Xataka | Scientists are intrigued by areas where people live absurdly long lives. The key was in Finland

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings