In 2019 we published a 37 minute documentary about Dulce, a girl with motor paralysis who learned to communicate using only his eyes and a system of eye-tracking by Irisbond. When she started with him, she was six years old. The learning process had just begun.

The eighteen months of recording culminated with a moment that summed up the entire effort: in front of her classmates, using her communicator, Dulce announced “my mother has a baby.” Pure manifestation of desires, willingness to share. Perhaps the first time he not only named the world but shaped it.

Six years later, we have spoken again with Raúl, his father. Today Dulce is thirteen years old, her brother Max is already ten, and Dante, that baby who was beginning to appear in Raquel, is already five years old.

The communicator is still your voice, but what has changed is what you say with it and what you use it for.

From spectator to teacher

When we met her, Dulce was learning to use the device with the patience of first Celia and then Mariano, her educators. He burst virtual balloons on the screen, related pictograms with concepts, constructed basic phrases.

The process was methodical and exhausting: each session required prior calibration, sustained concentration, and the diffuse promise that that, one day, would give him communicative independencesomething very remote then.

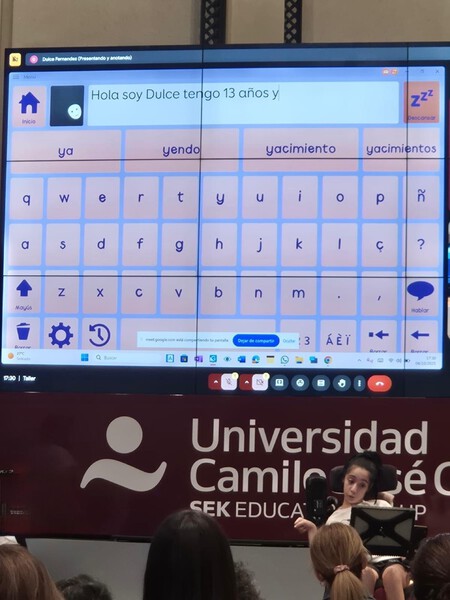

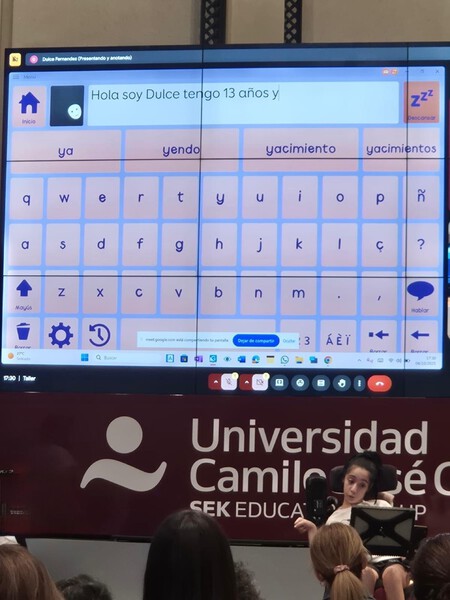

Dulce introducing herself at one of her talks. Image provided.

Now Dulce is on the other side. Not only does she now master the system, but she has become a trainer for other communicator users through Gema Canales Foundation. “She is as a teacher, teaching other children to use communicators because she is very good at it and has a lot of patience,” explains Raúl. “He’s taught three or four kids how to use the system already.”

It is not a specific activity. According to her father, it is something she would like to continue in the future, when she is an adult. The communicator is no longer just his or her tool of expression, but also what he or she trains others in.. The transformation is complete: from student struggling to articulate simple ideas to mentor capable of transmitting technique and patience to others.

Teenage conversations

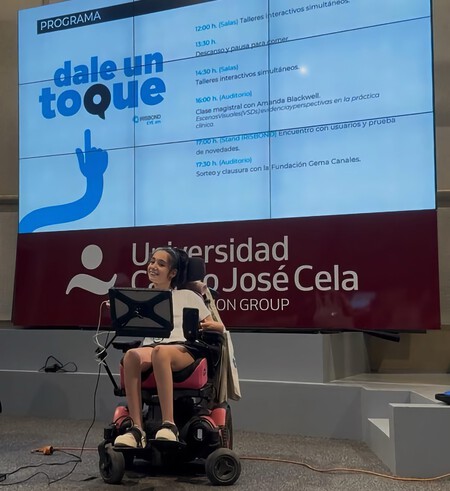

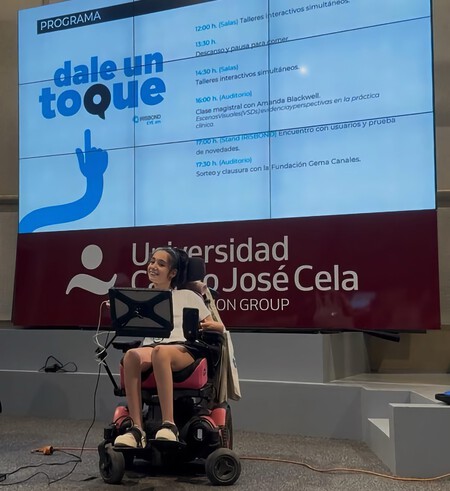

The most notable thing is not the technological leaps—which there have been, although moderate—but the communicative leaps. In 2018, Dulce was pronouncing single words, constructing short sentences and expressing basic desires. Six years later he has more complex conversations. “She has normal conversations of a 13-year-old teenager,” says Raúl.

Image provided.

The most notable change came with mobile phones. Dulce already has her own, not as the main communication device – for that she continues to use the Irisbond system connected to a tablet – but as a gateway to digital socialization typical of their age. The mobile allows you to access WhatsApp and have conversations with friends, a teenage rite of passage. Although he accesses through WhatsApp Web for fluidity and convenience, he also likes to use his cell phone with the mobility that his left hand allows.

This communicative autonomy has also changed its social dynamics. Raúl remembers moments when Dulce, in new environments with strangers, starts conversations using her communicator. The other kids quickly naturalize the system: “Oh, okay, I talk and she answers me like this.” There is no discomfort, just a slight adaptation to the pace of the conversation, which is slower than natural speech but fluid to maintain complete dialogues.

The voice that doesn’t want to change

Technologically, the system has not evolved a lot in these six years. The most important improvements occurred in the years before the documentary, when the eye-tracking It went from crude to functional. Since then, progress has been incremental. The response speed has improved slightly, the software is somewhat more predictive, but nothing transformative.

The most interesting thing is that Dulce has resisted changing the voice of the communicator. The system has been updated with more voices, even from children, not just adults, as some parents had been demanding.

Image provided.

When the tool added the first children’s voices, Raúl went “with all his enthusiasm” to configure it on Dulce’s tablet, but he found something unexpected: her refusal. She preferred to keep the one she has been using for years, with an adult ring. “She’s already gotten used to that being her sound. It’s like your voice changes overnight, you feel strange, you don’t recognize yourself in it.”

His father speculates something obvious but easy to forget: when you’ve spent most of your life hearing yourself speak in one way, changing your voice is not an improvement, it’s losing your sound identity.

The limit is still physical

Dulce finished primary education with excellent grades, with the only curricular adaptation in Physical Education. Now he is in 1st year of ESO and limitations are beginning to appear, not due to cognitive ability but due to motor demand. Mathematics, which in Primary was numbers, now introduces algebra. “There it could get more complicated for her,” admits Raúl.

The solution involves an assistant who transcribes what Dulce indicates with her communicator, a necessary support not because she does not understand the subject but because writing equations with her eyes is infinitely slower than by hand. It is a technical limitation, not an intellectual one, but it sets the pace of your academic progress.

The impact of the documentary

The 2019 report did not change Dulce’s life or that of her family. There was no media transformation or avalanche of attention. But Raúl remembers a very specific effect: when they had meetings with the Madrid Department of Education or made requests for academic support resources, someone would mention “ah, yes, you are Dulce’s family, the one from the documentary.”

“I already had a face, eyes, expressiveness, a story,” he explains. “It wasn’t just a name in a dossier.” In the bureaucratic negotiation for resources and support, this minimal humanization of the file worked in their favor. It wasn’t decisive, but it helped.

Image provided.

For the family, the documentary fulfills another function: It is the permanent record of unique moments. Dante, the brother that Dulce announced to her classmates in June 2019, has already seen how his older sister announced her arrival to the world. “It’s a nice memory to have it there, fixed; from time to time we see it again and we like it,” summarizes Raúl.

In 18 months, Dulce learned to speak with her eyes. In the ensuing six years, he has matured from childhood into pre-adolescence. Conversing, teaching, burning stages. The communicator stopped being your limitation and became your voice. And now, onto your work tool to help others find theirs.

In Xataka | ATMs and Amazon are on the verge of a great little revolution in Spain: the Accessibility Law

Featured image | Loaned

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings