On February 14, 2025, an explosive drone Shahed 136Iranian-made and possibly launched by Russia, pierced the structure of confinement at Chernobyl reactor 4, considered one of the greatest feats of modern engineering and designed to contain radiation from the worst nuclear disaster in history. Shortly after, Europe confirmed an open secret: plugging the “gap” was going to take a long time.

The consequence has now arrived: Chernobyl is once again a problem.

The impact and deterioration. The structure that was to guarantee a century of nuclear safety at Chernobyl has entered into a critical phase after the drone attack that pierced and burned he New Safe Confinementthe gigantic metal arch installed in 2016 to permanently seal reactor number four and contain any leaks of dust or radioactive gases.

The IAEA mission, after examining the state of the exterior coating, has confirmed that the structure has lost its essential function: no longer confines radiation as designed. The post-impact fire, which remained active for weeks When an impermeable internal membrane caught fire, it forced emergency crews to open hundreds of holes in the deck to locate embers, multiplying potential escape routes and further compromising the integrity of a system designed to be airtight for generations.

The “good”. That no increases have been recorded in the radiation levels in the surroundings, although the loss of tightness implies that an internal incident, even a minor one, could generate environmental dispersion in a complex where tons of radioactive material remain encapsulated inside the old Soviet sarcophagus, already exhausted in its useful life and never completely sealed.

The perforated sarcophagus

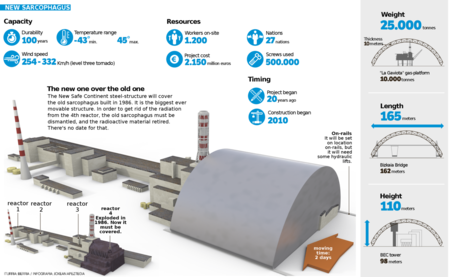

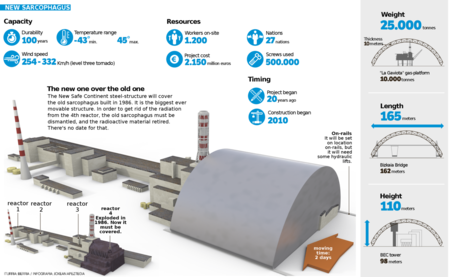

The fragility of a colossus. The sarcophagus is not just any structure: it is the largest mobile installation ever built, a metal arch as tall as a 30-story building and heavy as a battleship, financed by more than forty countries to allow (finally) the safe dismantling of the reactor destroyed in 1986.

Its mission was twofold: contain the toxic legacy of the past and provide a stable environment to remove, piece by piece, the remains of the molten core. But he february attack It opened a fifty-square-foot hole, damaged the main crane, and exposed a deeper problem: repairing a shield of this size and sensitivity is extraordinarily difficult.

The urgent thing. The most compromised areas are in areas where radiation prevents working normally, and moving the arch to intervene from the outside entails structural and exposure risks that still have no clear technical solution.

IAEA experts insist on the urgent need to control humidityreinforce anti-corrosion programs and plan permanent repairs before progressive deterioration turns the current situation into a cumulative risk.

An environmental threat. The impact of the drone, which Ukraine attributes to Russiahas not only left physical consequences on the structure: it has introduced a new vulnerability vector in an area that was already occupied in 2022, when Russian troops crossed the nuclear exclusion during their advance towards kyiv. Since then the enclave has become a symbol of the extent to which war can reopen dangers that Europe believed contained forever.

The loss of function of the shield does not imply an immediate disaster, how they emphasize both the IAEA and independent specialists, but it does increase the probability that an internal accident or a future incident will cause the release of radioactive dust towards an exterior that is no longer hermetically isolated.

Plus. The absence of leaks detected today does not reduce the severity of a deterioration that, if not corrected, can amplify any problem operational in a facility where dismantling work has been delayed for years precisely because of the war. The balance between technical stability, environmental risk and vulnerability to attacks is thus profoundly altered, in a context in which restoring security will not be quick, cheap or easy.

The technical challenge. The recommendations of the IAEA Director General, Rafael Grossi, insist on a complete and urgent restoration that stops the degradation of the shield and recovers its confinement function. However, the intervention it’s complicated: Handling damaged materials in a radioactive environment requires conditions that war does not guarantee, and moving the structure to work on it can generate mechanical stresses and unwanted risks.

Thus, Ukrainian authorities and international teams will have to decide how to act on a system designed to be immovable for a hundred years, now weakened by fires, drilling and prolonged exposure. Meanwhile, Europe is witnessing a strong reminder that nuclear infrastructure is not only vulnerable to the passage of time, but also to the dynamics of a conflict that has crossed all possible borders, including that of a disaster that forever marked the memory of the continent.

Image | State Nuclear Regulatory Inspectorate of Ukraine, Picryl

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings