Where you come from matters a lot if we talk about “social elevators.” Without going too far, the problem nuclear of housing for young people is not such depending on the family that has touched. But these inequalities begin to be noticed much earlier. In fact, it has been found that even the university degree itself does not depend so much on the grade, but on your origins.

Gap after the title. a study from the National Bureau of Economic Research with massive data on graduates from public universities in the United States show that, even when students have the same major, the same grades and leave the same institutions, those who come from low-income families finish five years later earning substantially less than their peers from families with more resources.

In other words, this means that graduating (which for years was the central objective of equity policies) does not close the gap, it simply transfer to the labor marketwhere he reappears strongly despite having followed the same academic itinerary.

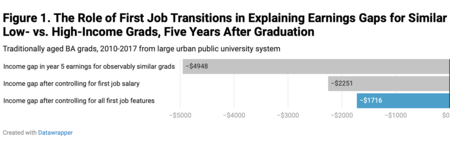

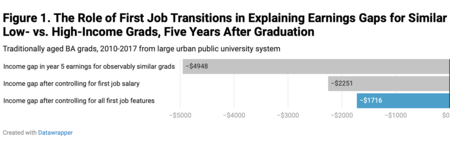

The first job. When the researchers adjusted the data by including characteristics of the first job (starting salary, company size, average employer salary level and sector) the gap between poor and rich graduates fell by a third of its original size.

This result indicates that a large part of the inequality does not occur years later, but in the instant of jump to the market: the first salary alone explains almost half of the income difference in year five, and other attributes of the first job destination added another substantial part. In other words, that first match between graduate and employer weighs more for future economic trajectory than most previous academic factors.

The differences. There’s more, as research indicates that graduates from lower-income households tend to reach the end of their degree less likely to have a secure jobaccept offers with lower starting salaries and enter companies that, on average, pay less and offer fewer promotion and training options.

Every extra thousand dollars in starting salary is associated with seven hundred dollars plus five years afterwards, and those who remain in first place for at least two years register several thousand more income in the medium term. This suggests that, even without differences in talent or record, the social origin determines the type of first job that is accessed, and that starting point chain conditions what happens later.

Implications. In a political key, the picture that emerges the work forces us to shift the focus of intervention: it is not enough to guarantee access and graduation if inequality re-establishes itself just as we cross the door of the labor market.

The researchers say that if the first job explains a good part of the gap, then the policy that aspires to real mobility must act explicitly about that transition (early information, networks, search preparation, paid internships, matching with better quality employers) because that is where today the nuclear difference is formed between equals on paper, but different in origin. Without that final layer, the title stops functioning as a ladder of equality and becomes a filter that validates inequalities that are already written before the first contract.

The weight of origin. In short, the evidence suggests that inequality reappears in the transition to work because the resources that mattered before university (social networks, early information, financial cushion and room to wait for a better offer) continue to operate when the time comes to choose the first job.

Those who can finance a few months without salary can reject bad offers and wait for a better one, and those who cannot, accept the first one. Those who have relatives or contacts in large companies obtain recommendations that reduce entry friction, and those who do not compete blindly. Even the most sensitive information about how, when and where to apply is unevenly distributed.

From that perspective, the “first step” is neither chance nor pure merit: it is a translation in labor terms of the previous advantages that are not seen in the academic record, but that determine the quality of the first contract, and of a “bright” future or simply a future.

Image | Pexels

In Xataka | The paradox of the “American dream”: the place where it is least likely to be achieved is the United States

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings