In recent weeks we have seen Elon Musk rising as champion of the neutrality of knowledgealthough paradoxically he does so by offering his own vision of history through an AI that only he controls: Grokipedia. Just like they stood out in The SixthMusk’s has not been the only case of a millionaire who has wanted to impose his interests on the interpretation of culture or how it is accessed.

For more than three centuries, millionaires have sought to influence in the way the world accesses knowledge, leaving traces that range from the Enlightenment to today’s digital world. Forms and formats change, from printed encyclopedias to artificial intelligence algorithms, but the intention to dominate the narrative persists.

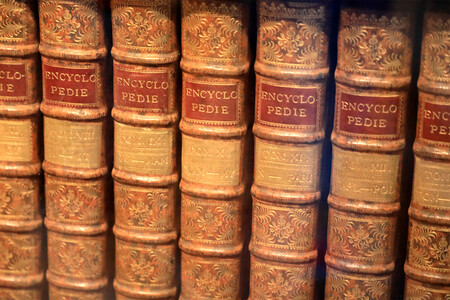

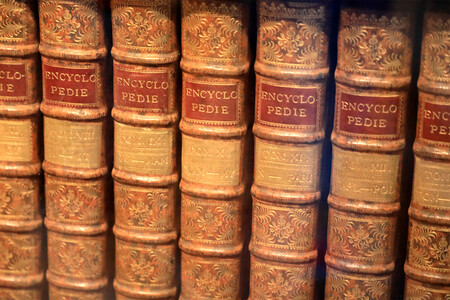

Chrétien-Guillaume de Malesherbes and the Encyclopédie

In the 18th century, the European political and religious context was restrictive and censorious with respect to knowledge that questioned religious dogma.

Chrétien-Guillaume de Malesherbeswas a wealthy and influential French official who, in his role as director of the Royal Librairie, took on the challenge to protect a work that challenged that order: the Encyclopédie of Diderot and d’Alembert. This ambitious project not only compiled human knowledge, but did so from a scientific and rational vision, displacing religious dogma from the center of knowledge.

The Encyclopédie became a symbol of the Enlightenment, an ideological statement that sought to liberate the human mind through reason and empiricismgenerating a profound cultural change against the dominant monarchical and ecclesiastical structures. Malesherbes faced censorship and prohibitions, but from his position of influence he defended evidence and science as bases for intellectual emancipation.

Encyclopédie of Diderot and d’Alembert

This approach not only transformed the way knowledge was understood in Europe, but also established a precedent: access to knowledge could be a tool for freedom and social criticism, very aligned (and even advanced) with the air of freedom that ran through France at the end of the 18th century. The Encyclopédie It was the first major initiative that reflected how knowledge could be a political and cultural weapon, shaped by those who had the influence to protect and disseminate it.

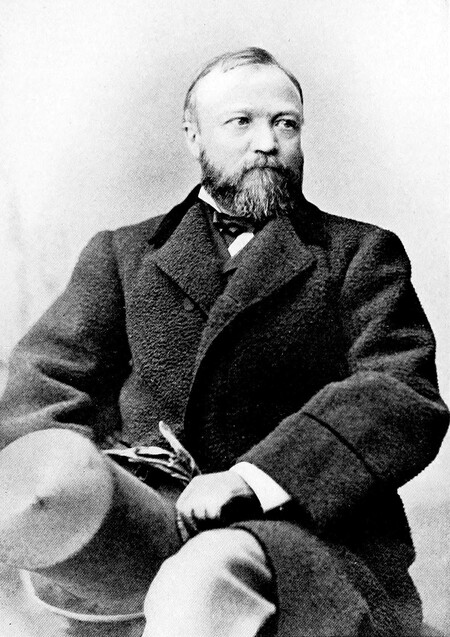

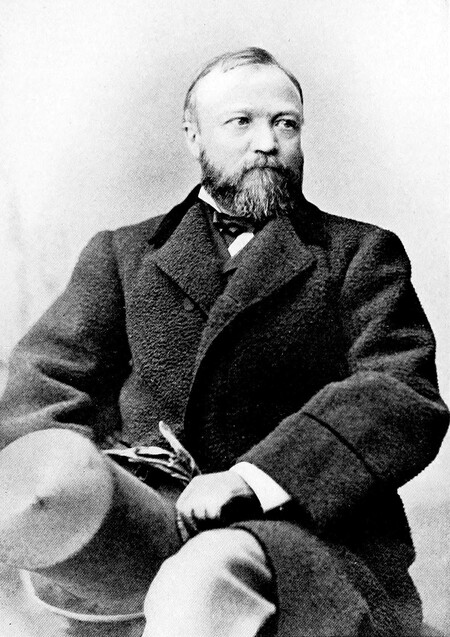

Andrew Carnegie and public libraries

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Andrew Carnegie brought the democratization of knowledge to a more tangible and accessible concept: free public libraries.

As and how do they count at the BBC, Carnegie was born into a working-class family in Scotland and emigrated to the United States where he amassed an immense fortune thanks to steel industry and demand for steel for railway construction. During his youth, Carnegie faced the reality that many private libraries charged fees that prevented access to the poorest, including himself, which motivated him to invest a good part of his fortune in establishing free libraries.

Andrew Carnegie in 1878

However, beyond his apparent philanthropy, Carnegie complained that many workers were not sufficiently trained, so his investment sought to bring that knowledge to the greatest number of people to create an educated and capable workforce.

Carnegie financed the construction and equipment of between 2,500 and 3,000 libraries leaving the communities responsible for its maintenance and operation, thus ensuring its sustainability. His vision was for the library to be an open-access community center so that everyone could educate themselves, so that foreigners could learn the language and acquire skills to boost industrial productivity.

Bill Gates and Encarta: knowledge in the digital age

With the computer boom in the early 90s, Bill Gates envisioned a new way to access knowledge: the multimedia encyclopedia. In 1993, Microsoft launched Encartaa CD-ROM encyclopedia that contained thousands of articles, audios, images and interactive maps accessible from a personal computer.

This product represented a radical change with respect to printed books and physical libraries, bringing information closer to homes around the world through technology. But Encarta was not an altruistic work to bring knowledge to users, but rather it set a clear commercial strategy: you needed a PC with Windows to use it, which promoted the influence of Microsoft’s operating system on the consumer.

Encarta was presented as an educational, useful and visually attractive tool for a diverse audience, reflecting the transition towards digital knowledge in the emerging Internet era. With this new product, Microsoft took a step back in the free access to knowledge for which Carnegie had fought: to learn with Encarta you had to pay a license between $395 and $22.95, depending on the year. Finally, Wikipedia came to break that economic barrier again by offering free and banishing Encarta.

Rupert Murdoch and the media narrative

While other models relied on encyclopedic or educational knowledge, Rupert Murdoch built a media empire focused on a more current concept: shaping public perception through ideological narratives.

Murdoch, the son of an Australian publisher, expanded his influence by controlling newspapers and television networks such as The Times, The Wall Street Journal and Fox News. His project was neither neutral nor purely informative, but rather a business model based on making the business profitable. opinion and ideological bias.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Murdoch built a media structure that made him tremendously rich. Instead of keeping informational neutralityshowed the news according to very defined ideological frameworks, with a focus on the interpretation of facts to influence public opinion. After all, it is another way of offering knowledge according to the point of view of whoever finances the medium.

Elon Musk and Grokipedia

In the 21st century, information flows in abundance through online channels, but even in this hyperconnected scenario, some millionaires continue to feel the need to show knowledge according to their own prism.

As part of his personal offensive against Wikipedia, Elon Musk has launched Grokipedia through his company xAI, presenting it as an alternative “without ideological restrictions or cultural biases” to Wikipedia.

Musk accused Wikipedia of having a “woke patina”, that is, a progressive cultural bias, and proposed Grokipedia as a project capable of offering “objective facts” generated by AI. However, Grokipedia has been criticized for reproducing specific political biases and by the lack of transparency in its sources that point to systematic copying of Wikipedia.

These five figures and their projects demonstrate how access to knowledge has always been linked to economic and political power. From the defense of reason against dogma, to public education, the digitization of knowledge, the construction of media narratives and artificial intelligence. The history of knowledge is also the history of its architectseach with their specific motivations and contexts that have left an indelible mark on the way we understand the world.

Image | Flickr (World Economic Forum, Gage Skidmore), Wikimedia Commons (Killer Cereals)

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings