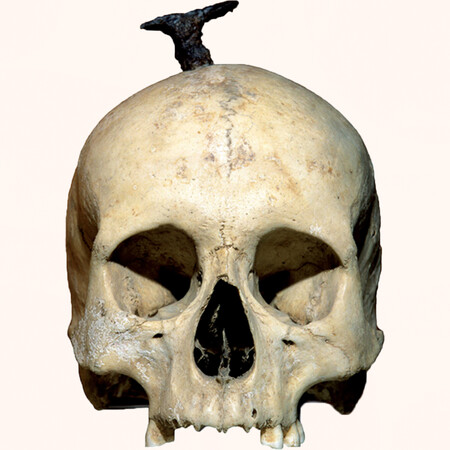

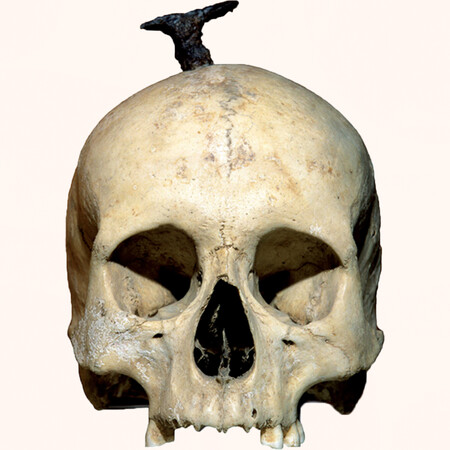

What does a severed head displayed on a wall mean? What if the skull also shows a huge iron nail stuck in the forehead? The question may sound crazy, but it has been intriguing archaeologists for decades who are dedicated to studying the communities that populated the northeast of the peninsula millennia ago, where have appeared in deposits like that of Ullastret. There are those who consider that the skulls were war trophies that were displayed as a warning and display of power. Others believe they are revered relics.

Now we are closer to find out.

What has happened? That archaeologists dedicated to studying the iberian communities of the Iron Age have delved into an enigma that has intrigued them for decades: Why the hell they cut off heads? What did they intend when they cut out skulls that they then exhibited to the public? Who owned them and what were they used for?

The issue becomes even more mysterious if we take into account that historians have verified that part of these decapitated skulls seemed to receive “a treatment post mortem“which included certain incisions or the use of cedar oil; and (perhaps most fascinating) that some skulls show enormous holes and even iron nails driven into the bone.

What exactly have they studied? What Rubén de la Fuente Seoane, an archaeologist at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, and his colleagues have done is to focus on two sites in the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula, located in what is now Catalonia: Puig Castellar and Ullastret. To be more precise, what they have analyzed are seven cut skulls located in both towns dated to the last millennium BC. Their conclusions have been expressed in an article published in Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

It may not seem like a very large sample, but skulls represent a much more widespread phenomenon. As I remembered this week Fran Lidz in The New York TimesSince 1904, archaeologists have located “dozens” of skulls of this type in the northeast of the peninsula dating between 800 and 218 BC.

You don’t have to go far to see them. They can be observed at the Museum of Archeology of Catalonia (MAC), which has been expanding your collection. The most curious thing is that these skulls were not only cut off, they were also exhibited, placed on porches, stakes… Sometimes with enormous iron nails pierced through them.

But… Why did they do it? That is the question that archaeologists have been asking for some time. Because? For what purpose were the skulls decapitated, prepared and displayed? “Who were these individuals and what were their heads used for?” he wonders From Fuente Seoane before remembering that “traditionally” the debate has revolved around two major hypotheses. There are those who maintain that the skulls were war trophies designed to intimidate enemies and those (in a radically different interpretation) interpreted them as “venerated relics” related to figures who had had influence in the community.

And what is the answer? Easy to ask, not so easy to answer. As you remember the article published by De la Fuente Seoane and his colleagues, some scholars have looked at the location of the skulls to try to understand their function. The problem is that this seems to complicate the issue even more.

There are heads that seem to have been displayed directly on walls. Others were discovered in graves or in the context of “domestic spaces.” How then to solve the enigma? De la Fuente-Seoane’s team chose to broaden the focus and avoid exclusive explanations. “Our study shows that it can be a mistake to have to choose only one option,” explains to The New York Times.

What does that mean? That the practice of severed heads among the Iberians of the northeastern peninsula could be richer, more diverse and complex than we thought. To begin with, the archaeologists confirmed that the skulls do not appear to have been selected at random. Some treatment is also appreciated post mortem of the pieces, with practices that suggest the existence of experts in preparing the skulls, which would in turn reveal that it was not an occasional practice.

“Our results reveal that the individuals from Puig Castellar and Ullastret would not have been selected at random. There would be a homogeneous tendency towards men in the ritual, but the patterns of mobility and location suggest greater diversity, which could imply social and cultural differences between individuals from the two communities,” comment. That is to say, experts suggest that the practice of severed heads could have responded to “several criteria.”

Same ritual, several meanings? Exact. “In Puig Castellar, severed heads in public spaces could demonstrate power, venerate prominent members of the community or intimidate enemies. In Ullastrer, the location of the heads in exposed areas suggests that they were important inhabitants, revered locally,” pick up the item. The ritual was therefore rich and more diverse than many believed. “It did not respond to the same symbolic expression among the Iberian communities of the northeast, It varied according to the settlement“.

“In some cases it seems that foreign individuals were mainly used as symbols of power and intimidation, while in other towns the veneration of individuals linked to the community could have been prioritized,” they point out from the UAB. “The practice of the heads was applied differently at each site, which seems to rule out a homogeneous symbolic expression.”

How did they conclude that? The researchers decided to study the origin of each skull and ask themselves a question: Did they belong to the native population or are they remains of people from other communities? It may seem like a minor issue, but it is crucial to the premise with which the team worked: if the skulls were war trophies they probably did not have a local origin, while if they were used to venerate ancestors of the community they surely did.

To clear up doubts, the experts resorted to the analysis of stable isotopes of strontium and oxygen in the dental enamel of the seven skulls recovered in Puig and Ullastrer. Their data was completed with other archaeozoological and “a detailed sampling” of sediment and vegetation collected in the deposits.

Did they discover something? Yes. With these clues the team determined which individuals had a local origin and which did not. “In Puig Castellar the isotopic values of three of the four individuals differ significantly from the local strontium reference, which suggests that they were probably not local. In Ullastrer we have found a mixture of local and non-local origins”, clarifies De la Fuente.

In the first town (Puig Castellar) the skulls were exposed in areas such as the wall, which leads archaeologists to think that they served to demonstrate power and dominance. In Ullastrer the two skulls of local origin were displayed on walls or doors of homes, as if they had belonged to someone revered. A third skull (of origin outside the community, according to the analysis) however appeared in a grave outside the walls, suggesting its value as a war trophy.

Why is it important? For several reasons. Beyond what it reveals to us about the ritual of severed heads, researchers they claim that the study shows “for the first time direct evidence of human mobility patterns in the Iron Age in the northeast of the peninsula.”

It is not a minor issue if one takes into account that archaeologists do not exactly have many funerary-type anthropological records to analyze Iberian communities. Its members practiced cremation, so the severed skulls represent “an exceptional opportunity.” Now thanks to the study led by the UAB we can better understand what they were used for.

Images | National Archaeological Museum

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings