In times where love seems to be summed up in a “swipe left” or “swipe right”, finding a partner has never been so easy… Or so difficult. While Tinder, Bumble or Hinge promise algorithmic compatibility, in China the most popular dating “app” does not require an internet connection, just a printer, an umbrella and worried parents.

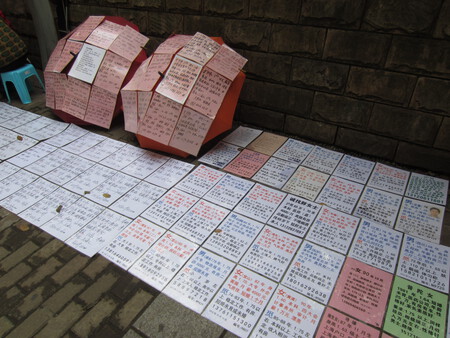

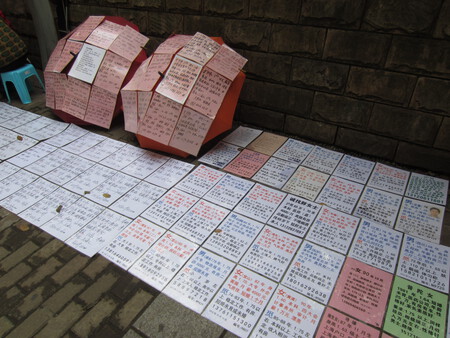

Every weekend, entire parks in cities like Beijing, Shanghai and Chongqing are transformed into a mosaic of laminated posters with personal descriptions. It is not the singles themselves who place them, but their parents. It is the so-called marriage market or xiangqin jiao (literally, “blind dating corner”), a phenomenon that can be described as an analog version of a dating app.

Love in times of demographic crisis. The rise of these markets has its origins in a paradox: while matching apps and agencies multiply, weddings and births plummet. In 2024, only 6.1 million couples will get married in China, 21% less than the previous year and the lowest number since records began. according to data from the Wall Street Journal. This year there was a small rebound — 3.54 million marriages in the first half — thanks to a new policy that simplifies civil registration according to the South Morning Post. But the general trend continues to plummet.

The causes of this situation they are multiple: long working hours, high housing prices, gender inequality and, above all, new priorities among young people. “Energy is limited, so I eliminate what drains me the most. First thing? Dates,” confessed a 22-year-old studentreflecting a profound generational change. Faced with this scenario, many parents decided to move from concern to action: if their children are not looking for a partner online, they are looking for one in the parks.

How does the Tinder of paper? According to Noema Magazinethe first love market emerged more than a decade ago in Shanghai, in People’s Park. Every Saturday and Sunday, no matter rain or shine, the park is filled with parents with signs hanging on ropes, benches or open umbrellas. They detail age, height, weight, salary, property, including whether the candidate’s parents have a pension. Photos, interestingly, are optional. “Those who do it best are the average ones: neither very good nor terrible,” explained a matchmaker nicknamed the Professor Guwhich charges the equivalent of $16 to display a poster for six months.

In Chongqing, another of the large cities of the southwest, The Wall Street Journal described similar scenes: retired parents squeezed on paths covered with posters. Some attendees use WeChat — the ubiquitous app in China — to scan QR codes or exchange contacts. A woman included in her profile that she earns $560 a month, that she owns a house and a car, and that she is looking for a husband “without bad habits, under 29 years old and no taller than 1.73.” On the next page, a 26-year-old man asked for a wife with a university education and “who is not too plump,” a reflection of still very traditional standards.

The cultural contrast is evident. In China, marriages are still considered an economic and family alliance rather than a romantic act. Therefore, the marriage market is, as detailed in Noema Magazine“a fusion between Match.com and a farmers market,” where banners replace digital profiles and parents act as human filters.

Marriage market in Shanghai

Is love found? Really, few achieve success. The stories of couples formed under this phenomenon They are almost non-existent. Most return every weekend out of habit, for company or simply to kill time. A father from Shanghai, interviewed by The Agehas been there for more than a year and has only gotten two matches for his 36-year-old son, with no results. “I only act as an intermediary, I pass the information on to him, but in the end it depends on him,” he confessed resignedly.

Despite everything, for many it is a form of generational catharsis. “Our kids think ‘why should I settle?’” said a woman nicknamed Sister Gaoa veteran matchmaker who arrives every week with dozens of laminated profiles. “In our generation, people put up with more. Today they don’t want to tolerate anything.”

There are also young people who challenge the norm. As reported by the state media CGTNHuang Junjie, 29, decided to advertise himself in the Beijing market. “I tried apps like Douyin or Xiaohongshu, but they felt very far away. Here at least you see people face to face,” he explained, standing next to his sign. He was looking for a mature woman and was even willing to get married. matrilocal —living with the wife’s family—something unthinkable a generation ago.

Beyond love. Behind every umbrella is a story of anxiety and family pride. In China, many parents feel that seeing their children married is their last mission in life. In a society where being single is perceived almost as a failure, the markets They are both a space of hope and shame. For this reason, some parents They confessed to feeling humiliated for having to “offer” their children in public, although others defended their right to intervene. “The girls are not willing to say ‘I want a boyfriend’, so we help them,” said a mother from Shanghai.

In essence, the phenomenon also reflects loneliness of an older generation. With more than 300 million retirees, many of them widowed or divorced, attending the love market is also a way to socialize, not to be left alone at home.

Meanwhile, the Government is trying to stop the decline in marriages with economic incentives, child subsidies and even university courses on “romantic education.” But, as analysts point outthe results remain modest: young people value personal freedom more than the pressure to get married.

A pressure for women. In this scenario, women bear disproportionate pressure. In China, staying single beyond the age of 27 can make you a Sheng Nuliterally “leftover woman.” The term, popularized by state media in the 2000s, became a social stigma that pushes many professionals to justify their singleness to their own families. According to The Washington Postsome even resort to “how to find a boyfriend” courses or luxury matchmaking agencies that charge thousands of dollars to guarantee a “proper” marriage. Others simply refuse to give in to pressure. “It’s not that we are demanding,” said a woman interviewed in Shanghai, “it’s that they are not up to par.”

A difficult panorama for love. In the parks of China, between umbrellas, laminated posters and parents playing Cupid, love seems to be torn between tradition and the algorithm. Marriage markets are not just a cultural curiosity: they are the reflection of a society that ages, individualizes and seeks a solution for the future in the methods of the past.

But on second thought, perhaps this is not just a Chinese dilemma. In a world where loneliness grows at the same rate as dating apps, we are all a little bit in search of the perfect “match”—even if it is outside of Wi-Fi. And seeing how things are, maybe it’s not such a bad idea to take my parents to the park.

Featured image | JP Bowen

Text image | Another Believer

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings