Historians have been trying for decades free her from her bad reputationbut it’s still hard not to feel a pang of compassion when one thinks of the Middle Ages. Logical. We have been burned with the idea that it was a time of wars, epidemicsfamines, wars and superstition in which humanity moved away from the advances of previous centuries to throw itself into the arms of barbarism.

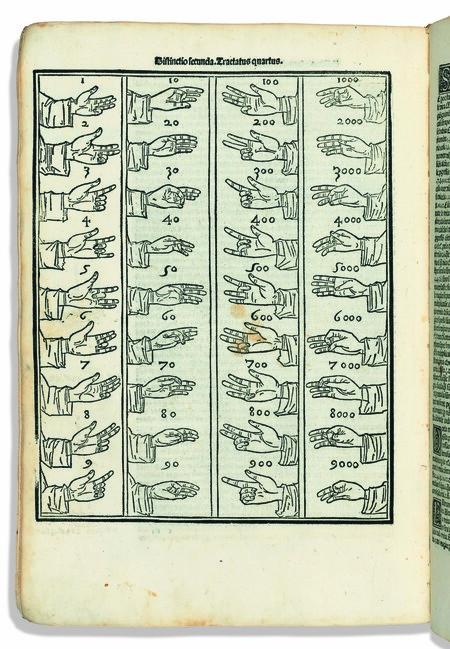

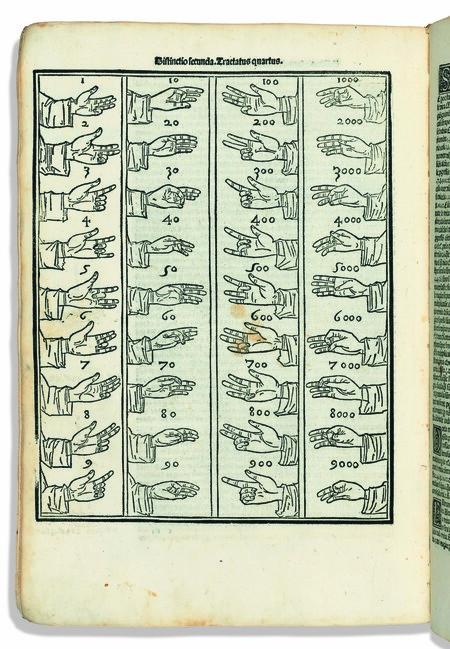

Things change when you find out that an 8th century monk was capable of doing something that will probably seem impossible to you (and most people): count up to 9,999 with your handsrepresenting any number with just your fingers.

Count with your hands? Exact. If we keep doing it in a rudimentary way (and limited) today, in a time when almost everyone walks around with a phone in their pocket, imagine how important the art of counting on your fingers was centuries ago. How do you do addition and subtraction when you have nothing to rely on? And by nothing we do not mean a calculator or a primitive abacus, but tools as basic as paper and a pencil or pen to take notes.

For centuries those who wanted to do calculations were content with what was closest to hand. And usually that was (pardon the redundancy) his own hands, his 10 fingers and the universe of combinations that opened up his joints and, above all, his imagination. The result is an ancient art that has fallen into disuse over the centuries, but came to acquire an astonishing level of perfection. In fact it can date back to ancient times, long before the Middle Ages.

One name: Bede Venerabilis. If we know the peculiar way our ancestors had to count astronomical figures with their fingers, it is thanks largely to a Benedictine monk who lived between the 7th and 8th centuries in what is now the United Kingdom. His name: Bede, although he is usually known as Saint Bede the Venerable. In 725 the religious wrote ‘De temporum ratione’ (‘The Calculation of Time’), a treatise that talks about the cosmos, calendars and the best way to calculate the date of Easter, a relevant topic in its day.

Before addressing most of these questions, the author however touches on a simpler and more important question: “De computo vel loquela digitorum”how to make beads with your fingers. Bede does not expose us to a system devised by him, but rather he describes to us a practical art that has its roots long ago.

The power of one hand. “Before we begin, with the help of God, to talk about chronology and its calculation, we consider it necessary to first briefly show the very necessary and practical technique of counting on the fingers,” starts Bede in the first chapter. From there it goes on to explain how we should place our fingers to show the numbers from 1 to 9,999. By complicating the system a little more you can reach 999,999. There is even a symbol for the million

“Somma di arithmetica”, by Luca Pacioli.

And how the hell do they do it? With imagination, ingenuity and also a certain agility with the hands. Especially if what we want is to represent high figures. In Scientific Culture UPV/EHU mathematics professor Raúl Ibáñez signs an interesting article which details how the system works, including graphics and translated quotes from Bede himself, who first explains how to place the fingers of the left hand to represent low numbers.

“When you say one, bending the left little finger, place it in the middle joint of the palm. When you say two, bend the second finger placing it in the same place,” clarifies the Benedictine monkwho continues patiently explaining to us how to show figures with the left hand, move to tens or make the jump to hundreds and thousands with the help of the right.

The key is in the meaning of each hand and groups of fingers, which are assigned the value of the units of thousands, hundreds, tens and ones. If we want to go further and express tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands we will only have to vary the position of each of the hands with respect to the body.

Beyond the Middle Ages. In a video published in 2020 by the BBC, Seb Falk, author of ‘The Light Ages’, also explains how centuries ago they managed to represent astronomical quantities with their fingers. The most surprising thing is that the system long predates Vera. “It was used from Roman times to the Middle Ages (11th to 13th centuries) throughout Europe,” says the historian.

“Just as when we write we have a column for units, another for tens, for hundreds and thousands, they dedicate the little finger, ring and middle fingers of the left hand to the units and the index and thumb to the tens. On the right, the thumb and index indicate the hundreds and the other fingers, the thousands.”

In short: ten fingers, 9,999 numbers. It’s all a matter of internalizing the system, understanding its dynamics and playing with positions. The truth is that the method is so curious that it has aroused the interest of authors after Bede, such as the mathematician Jacob Leupoldwho addresses it in an 18th century treatise; or the famous Luca Pacioliwhich refers to (with some changes) in ‘Summa’.

Why get so complicated? At a time when we are accustomed to walking with smartphones (with their respective calculators) in their pockets and it is not difficult to find paper and ink, perhaps we will be surprised by the system that the Venerable Bede tells us about. Things change when we think about the resources they had available centuries ago. And the range of possibilities that such a system opened up, which only needs something as simple and universal as the fingers of the hands.

“It was a code, a sign language, that was used in markets, as it was an effective way to communicate in the middle of noise and at a distance,” Falk relates.who remembers that even today it is not strange to see stockbrokers making signs to each other. “Those who used it the most were the monks, not only to communicate in the monasteries, where silence was precious, but they used their hands to memorize philosophical texts and mathematical formulas.” Bede himself recognize that if the numbers were changed to letters it was used to send encrypted messages.

Images | Wikipedia 1, 2 and 3

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings