There are many reasons to look for a cement substitute, but one of the most important is that your industry is responsible. 7% of global CO2 emissions. Thus, we have already seen moderately viable solutions with ecological mortar and even with shellsbut the Federal Polytechnic School of Zurich has been looking for its replacement in nature for some time. Better said, in living materials such as bacteria, algae and fungi. And he has found it precisely in cyanobacteria. It sounds strange, but it has more advantages than it seems.

The challenge of replacing concrete. In an industry that revolves around classic materials such as steel, concrete or cement (which, after all, is part of the cement recipe), the search for a replacement entails great implications in terms of infrastructure and costs.

Assuming that the minimum expected is that it has similar mechanical characteristics, the search for an alternative involves a material that is better, since the manufacture of traditional concrete consumes a large amount of resources, the pollution is very high and it also degrades over time.

This concrete is alive. Literally. The research team has managed to stably incorporate cyanobacteria into a printable gel to develop a living photosynthetic material that nourishes, grows and removes carbon dioxide from the air in the process, as detailed. in Nature magazine.

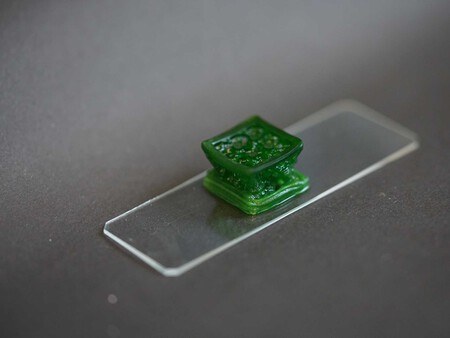

This material can be molded with 3D printing and requires sunlight, nutrients from artificial seawater, and carbon dioxide to grow. The matrix is a water-rich hydrogel composed of cross-linked polymers with a geometry such that it facilitates the transport of light, carbon dioxide, nutrients and water. That is, so that cyanobacteria live longer and better.

From passive material to carbon sink. Concrete is also a passive material, that is, once fixed in the structures it stays there, degrading over time. So ETH Zurich has proposed a paradigm shift in which buildings go from being an inevitable source of emissions to becoming an active organism that can clean the atmosphere, something like a plant. Thus, the biotechnological system is made up of cyanobacteria integrated into the matrix of the material, so that its structure protects them while they perform their function.

On the one hand, by minimizing the use of cement, you reduce process emissions. On the other hand, it not only stops emissions: this system sequesters atmospheric carbon permanently in its structure. And it is no small thing: according to Yifan Cui, one of the two main authors of the study, “the material can store carbon not only in the form of biomass, but also in the form of minerals, a special property of these cyanobacteria.” However, cyanobacteria are one of the oldest forms of life on the planet and are extremely efficient at photosynthesis.

The “magic” equation of photosynthesis. When microorganisms absorb carbon dioxide with sunlight, a biomineralization process is carried out by which this dioxide turns into calcium carbonate, reinforcing the structure of the material with this mineral, which also has the ability to store carbon dioxide in a more stable way. In its laboratory tests, in 400 days the material was able to store 26 mg of CO₂ per gram of material, notably more than the 7 mg of CO₂ per gram of recycled concrete.

A concrete that “heals” itself. This generated mineral becomes a glue that holds everything together, improving its structural integrity over time. Something that is inevitable about concrete is that it cracks, but in this case, when microcracks appear, the entry of moisture and oxygen reacts to the bacteria, which secrete this mineral to seal it. In short, it heals itself. This healing capacity is an asset in terms of maintenance costs, minimizing corrosion of reinforcing steel in hybrid structures.

There is already cyanobacteria concrete. Moving from the laboratory to the real world is a critical process that this project has already successfully overcome: in the Venice Architecture Biennale Several large blocks can be found (the largest is three meters high) in the exhibition. Be careful because, as they detail, each of these blocks is capable of storing up to 18 kilograms of carbon dioxide per year, rivaling with an adult tree.

And now what? As explains Mark Tibbit, Professor of Macromolecular Engineering at ETH Zurich, Mark Tibbitt, in the future want to study “how it can be used as a façade cladding to capture CO₂ throughout the entire life cycle of a building.” For it to go from being a laboratory project with samples in exhibitions to reality, challenges such as scalability and costs, as well as mechanical properties and the survival of the bacteria, will have to be faced.

In Xataka | We had been looking for an alternative to cement for decades. We just found it in seashells

Cover | ETH Zurich

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings