It is the fundamental question: how did it all begin? How, on a young, chaotic, geologically active planet, does a handful of inert chemistry became the first living cell? What we know is that the protocell, called LUCAstarted life and Darwinian evolution did the rest, taking us to the present day. But there are still many questions about why all this arose.

The mystery. We really know little about our origins. But we are not referring to whether we come from a monkey or another species, but from why did life begin on this planet. Something that wanted to solve the study by Robert G. Endres, of Imperial College London, but which has only given us many more questions and even a bad taste in our mouths, because according to their results, life should not have arisen.

And by applying mathematics, that branch of science that many people hate, a very clear conclusion has been reached: the barriers for life to arise spontaneously are “formidable.” So formidable, in fact, that the odds of it occurring by pure chance within the window of time available on the early Earth are astonishingly low, meaning that it would have been logical that life would never have arisen.

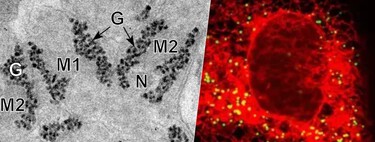

Software of life. Endres’s approach leaves out test tubes and focuses on information. A cell is not just a “bag of molecules”; It is a highly structured and orchestrated system over time and related to each other. The question is: how much information is needed to “write” the first protocell that gave rise to life?

To estimate it, the study uses modern computational models and AI tools that we already use today, such as AlphaFold (for protein folding) and full “whole cell” models. The result in this case was divided into three different parts:

- The genetic information for a very simple cell like Mycoplasma genitalium occupies 10⁶ bits, which is quite little.

- Structural information, that is, how proteins fold and the cell is organized, is also estimated in a range of 10⁶ to 10⁸ bits.

- Finally, dynamic information, which focuses on metabolic pathways, signaling or DNA replication mechanisms, which is undoubtedly a giant. In this case a value of 140 MB has been given in this world that has been generated.

Adding all this together, the complexity of a simple protocell has been estimated at 1 billion bits in software simile. And that is the wall that prebiotic chemistry had to end up climbing.

The mathematics. Once you have all the theoretical information, this is where the mathematics becomes very interesting, especially considering that the Earth had a ‘window’ of time available to accumulate all this information. 500 million years until the first protocell was given. In a very simple account, if you divide the necessary information (10000000000 bits) by the available time, you get the minimum information accumulation rate of 2 bits of useful information per year.

Seen like this, it seems very easy! The study estimates that the prebiotic “soup”, full of complex molecules, had the potential to generate information of about 100 bits/s, billions of times more than necessary, according to mathematical estimates. So… Where is the problem if there was plenty of time?

The problem is that these ‘2 bits per year’ are assumed to be a unidirectional and progressive process. That is, when that piece of useful information is created, it is saved and used for the next step. But chemistry is a chaotic soup that does not work like that, but rather works like a ‘random walk’: you take one step forward and then another step back. That is, when creating something it is accompanied by a loss.

This is where the concept of ‘persistence’ comes in, which in short is the time during which the system “remembers” the information it has gained, even if it has been lost. In this way, without immense persistence, the emergence of life would be literally impossible to occur according to this study.

The push. But looking at mathematics, in a soup as chaotic as this one, the reality is that leaving everything to chance would have meant that we would never have been able to appear on this planet. And this is the real mystery. For us to be here, there had to be some physical principle, a chemical bias or some ‘memory’ or ‘retention’ mechanism that gave directionality to the process.

The study does not say that life is impossible, but that the mechanism Purely random is insufficient. We need “unknown physical principles” or, as the author points out, “some form of prebiotic informational structure.”

And it is something that is raised in other studies, such as that of Chrostoph Adami who focused in trying to understand living beings as self-sufficient chains of information to search for the probability that life emerges in a statistical manner. And it is also found with a very low probability.

The aliens. It is at this point of mystery that the article cautiously mentions the alternative hypothesis: directed panspermia. Originally proposed by Francis Crick (the discoverer of DNA) and Leslie Orgel, it suggests that an advanced extraterrestrial civilization intentionally “seeded” life on Earth. Although this idea violates the Ockham’s razor (the simplest explanation is usually the correct one), the author admits that it remains a “logically open” alternative.

Artificial intelligence. AI has had a lot to say, since thanks to its capabilities it has been possible to estimate the algorithmic complexity of the cell that gave rise to life, giving us the scale of the problem. And the author points out that AI could also be the key to the solution, since he proposes tools that could ‘help reverse engineer candidate pathways’. That is, it could be the one that finally finds that ‘push’ that we don’t know about at the moment.

Images | Laura Seaman

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings