After escalating during the pandemic to higher levels of its history, the price of rent in the United States started to retreat for the first time in years. The shift is neither punctual nor local: it is now observed on a sustained basis in most large cities and has lasted long enough to be considered a phase change in the market, not a seasonal blip. The question seems clear: why on earth did the rent begin to be transferred precisely now and not before?

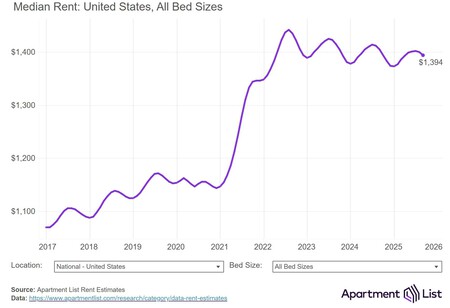

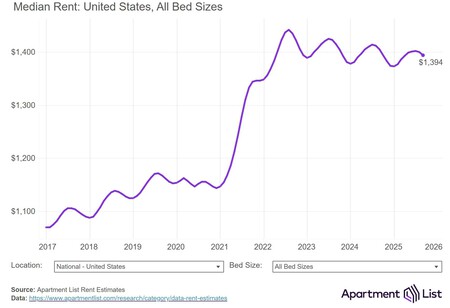

An unusual twist. After two years of historic increases driven by the pandemic shockrents in the United States have almost three consecutive years correcting National data places the average rent 3-3.5% below from the maximum of August 2022, with interannual decreases chained in the 50 largest markets.

That correction is striking for a reason. very simple: It occurs in a country with a chronic housing deficit and with a still stressed cost of living. It is not a collapse, but a normalization after an extreme phase: because even with the decrease, the typical rent is still 20-22% above 2021.

Austin as a laboratory. It we count a few months ago. Austin possibly offers the compressed version of what has happened on a national scale: after a boom in demand (internal migration, arrival of companies, cheap credit), the market responded with an expansion of unprecedented offer (an increase of more than 8% in the housing stock in a few years, with permits at rates that surpassed other comparable cities) and a subsequent slowdown due to the rapid rise in interest rates.

The combined effect has led to rent drops of 22% from highs and sales price declines of 10-18%. The Austin case demonstrates that when the bottleneck is attacked on the supply side, the price falls before demand is destroyed due to poverty: it cools due to saturation, not due to collapse.

National evidence. The pattern is common: in 2024 they were delivered more than 600,000 homes multifamily, the largest flow since 1986. There are still 686,000 under construction (well above the historical average) and 7.1% vacancymaximum of the series.

A greater number of competing units forces prices to be lowered or free weeks to be granted to accelerate occupancy. The time that passes from when a home is published on the market until the contract is signed with a tenant now takes longer: 31 days on average compared to 19-20 days at the peak of tightness in 2021. The macro result is the loss of owners’ ability to raise prices in a market where the tenant has regained the margin of choice.

Fall mechanics. The 2020-2022 phase combined demand shock (sudden migration + very low rates + change in preferences) with insufficient supply After a decade of under-construction post-2008, the price rose. In 2023-2025 reverse the asymmetry: the pipeline (the set of homes in the process of entering the market, but that have not yet become available) during the boom is delivered just when demand is cools due to high rates and the return of some migratory flows.

What happens then? That the excess of units leads to greater vacancy, and vacancy is the nuclear variable that sets the price: after a certain threshold the expected income per empty unit falls more than it is worth keeping the rent high, and the owner adjust the price before than empty time. The fall is not structural but cyclical: if the supply were to stop completely, the pressure would return, as analysts already warn in the same Austin case.

Uneven geography. The most intense decreases are concentrated in the Sun Belt markets (Austin, Phoenix, Denver, San Antonio, Orlando, Dallas), where production was faster and vacancy was higher. Markets with expensive land and regulatory barriers (cities such as San Francisco, New York, the NE coast and some Midwest nodes) show even rises because there the supply adjustment arrived late or simply did not arrive.

This also confirms the direct relationship between the pace of permits/construction and price moderation: where construction was allowed, the rent fell, and where it was not, it continued to rise.

It’s a correction. Most analysts agree on the same explanation. Despite the “rents are falling” narrative, the benchmark matters: the current absolute level is still well above pre-COVID, and the rent-to-income ratio has only returned to “manageable” zone (~23%) in a section of cities, and in areas like Miami or the NE coast it is still overflowing.

That is why the experts they underline That anyone who expects to return to 2019 prices does not understand the basis: the new housing built is higher because the cost factors (land, insurance, construction, structural inflation) have not reversed, which suggests that the downward phase has a ceiling.

Exportable lesson. The factor that can be copied is not the United States Federal Reserve or migration, but rather the supply elasticity: Austin proves, with an example empirical and measurablethat by authorizing and delivering new housing in large and sustained volumes, the rent stops being a fatalistic variable and begins to behave as an acceptable price due to competition.

The rest of the country reproduces the same pattern where supply entered on a scale, and where it did not enter, the price simply did not weaken.

Image | Pexels, Eric R. Bechtold, Apartment List

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings