Hundreds of thousands of years of evolution They have turned modern humans into perfect machines in one thing: distracting us. No matter where, when or how you are, if you are accompanied or alone, if you are waiting in line at the butcher shop or have a book in front of you, chances are that your attention ends up dispersing for any nonsense. Maybe the flight of a fly. Maybe that sound you just heard in the next room or a stain on the wall.

It happens today and it happened a century ago, when a science fiction-loving inventor designed the ultimate machine to end distractions. His patent dates back to 1925, but it addresses a hot topic: procrastination.

The war of wars. Since man has been a man, he has done two things, both wonderfully: he is distracted and he procrastinates. Almost 2,000 years ago Seneca warned us about the risks of wasting our time and we know, for example, that distractions were one of the big concerns of the monks of the Middle Ages. Some even thought that if our minds disperse it is due to the influence of devils. In 2026 things are not very different.

A quick Google search comes up to find a wide (very wide) list of guides and videos with tips on how to focus and stop putting off tasks. And it is understandable. After all, cell phones, social networks and other inventions of modern technology make our lives easier, but they have been filing our ability to focus. Even science has confirmed that we are losing the ability to focus among so many stimuli.

And how do we solve it? We humans have not only been distracted for centuries and centuries. We have also spent some time looking for ways to avoid that annoying wandering of thoughts. Of all the solutions that have been given to the problem, perhaps the most astonishing (and bizarre) is the one proposed just a century ago by Hugo Gernsbachan imaginative Luxembourgish-American inventor.

His name may sound familiar to you because, in addition to register patents of inventions and working in the electronics industry, Gernsback excelled in another field: publishing. Throughout his life he promoted several magazines focused on technology (RadioNews), but he also shone in science fiction. We owe him Amazon Storiesa milestone of the genre. His contribution in the field was so important that he is considered one of the parents of science fiction (with permission from Verne and HG Wells) and every year he is honored through the Hugo Awards.

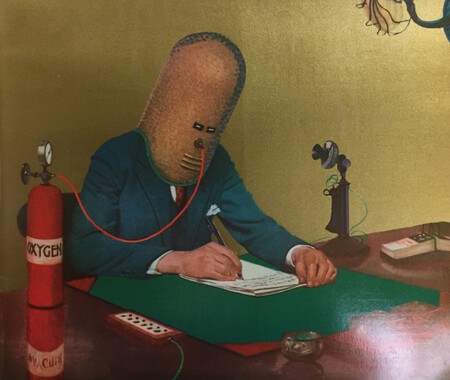

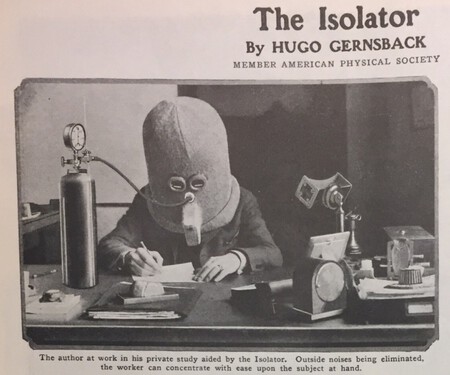

Adding facets. A century ago Gernsback combined this double facet, his technical ingenuity and overflowing imagination, to launch a proposal through the pages of Science and Inventiona magazine specialized in technology. In its July 1925 issue, the inventor, editor and novelist presented a creation which he named ‘The Isolator’. The name is striking in itself, but it pales in comparison to the photographs that illustrate the report.

They show Gernsback working in his office with his head in a gigantic diving suit, an elongated helmet with two small openings for the eyes and a tube that connects it to an oxygen cylinder. Its purpose: to immerse the wearer in absolute isolation, an ideal state for centering.

When silence does not come. Gernsback came to a conclusion very simple: sometimes it is not enough to lock yourself in a room without noise to concentrate. Even so, we risk our mind getting carried away by the flight of a fly or starting to wander after seeing a stain on the table. The way to avoid it, he concluded, was to eliminate all those influences “in one fell swoop.” As? With a helmet prepared to suppress unnecessary noises and visual stimuli.

For the first thing, the noises, Gernsback decided to go for a robust multi-layer helmet. Its first prototype was made of solid wood with an internal and external layer of cork and a felt trim. For the second (view) he added three small pieces of glass. The design was completed with a device at mouth height that allowed the user to breathe without noise creeping in.

The result, says the inventorit was a helm with an efficiency of “about 75%”. It isolated from external noises, but not completely. There was room for improvement.

And how did you improve it? Perfecting the design. Gernsback rethought the material and added an air chamber so that the efficiency of ‘The Isolator’ rose to 90 or 95%, “eliminating practically all noise.” So that vision was not a problem either, the helmet’s glass peepholes located in front of the eyes were painted black, leaving only a narrow transparent strip.

“When the two white lines on the glass open, the field through which the view can move is relatively small,” points out the inventor. “It is almost impossible to see anything but a sheet of paper in front of the user. There is no distraction.”

Concentrating… and breathing. It is one thing that ‘Isolator’ lived up to its name by isolating the user in a bubble of responsible concentration and another, very different, that it was comfortable or even bearable. The author explains that after 15 minutes with it on the user “experienced some drowsiness”, so he decided to improve the breathing system, connecting it to a small oxygen tank. This improved breathing and “revitalized the subject.”

In his article Gernsback added detailed plans of ‘The Isolator’ and even a sketch of an office with a complete distraction-proof installation, which included a ‘noise-proof’ door and an adequate ventilation system. “With this provision you can contemplate an important task in a short time,” boasted. “Building ‘The Isolator’ will be a huge investment.”

The power of paper. If humanity has also learned something (including Gernsback) it is that paper supports ideas that are not supported in reality. His helmet may have been eye-catching, it may have even worked, but it didn’t work.

We don’t know to what extent its inventor really expected it to work on a commercial level, but it seems that ‘The Isolator’ did not arouse passions. Publishers Weekly assures that only 11 were built, so the idea remained just that: the idea of an imagination passionate about technology and fiction.

IFL Science slide also that the contraption had some weak points. Specifically, it talks about air flow. “It’s a little more complex than installing an oxygen nozzle. Excess oxygen can be toxic, but without sufficient gas flow and proper ventilation, CO2 buildup is a much more likely and serious complication,” prevents R. Funnell, editor. The challenge was therefore to guarantee the entry of oxygen and eliminate CO2.

Images | University of Minnesota Twin Cities

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings