In a corner of Southeast Asia, the island of Borneo has been the scene of a historical entanglement that seems like something out of a novel. What began more than a century ago as a trade agreement between a local sultan and European businessmen today translates into multimillion-dollar lawsuits and international arbitrations involving Spain, Malaysia and the descendants of the Joló sultanate.

The surprising thing is that the origin of all this mess goes back to a detail that many would overlook, but given that when it happened the island was under Spanish jurisdiction, a century and a half later, the judicial imbroglio has spilled over into a Spain that has been involved in a lawsuit for 15.5 billion euros without a hitch.

Signing of the agreement and colonial movements

In 1878, the island of Borneo was under Spanish administration in certain areas, although real authority corresponded to the Sultan of Joló, the highest authority in a small Muslim kingdom located to the north of that island.

In that year, Sultan Jamalul Alam signed an agreement with two British businessmen, Baron of Overbeck and Alfred Dent for the exploitation of natural resources of the area. However, for the descendants of the sultan, that contract had a lease character, while for the British it implied a definitive transfer. First point of disagreement.

Spain, as the administrative power of the time, left evidence of its limits and neither punctured nor cut nor cut in that agreement.

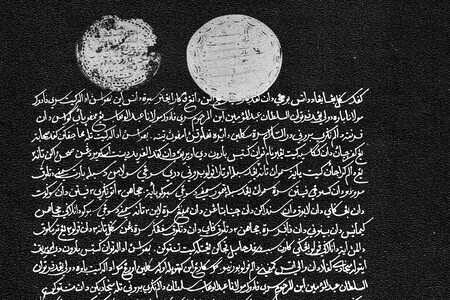

Reproduction of the 1878 agreement

In 1885 the Madrid Protocol between the United Kingdom, Germany and Spain, with which Spain formally renounced any right over Borneo and recognized British control of the area, left in hands of the British North Borneo Company to its colonial exploitation and became part of the British colonial territories.

Already in 1963, the island of Borneo was integrated in the newly formed Malaysia, and the Joló sultanate was integrated as the state of Sabah. Under the agreement signed in 1878, the Malaysian government was the “heir” of that transfer/lease of the territory, so kept a symbolic payment annual payment of about 5,300 ringgit (about 1,110 euros per year at the exchange rate) to the sultan’s heirs.

However, in the 1980s and 1990s, oil and gas deposits were discovered in that territory, so Malaysia, through the company Petronas. With a treasure of such magnitude under the soil of their territory and with a difference of opinion regarding the meaning of the initial agreement, the heirs of Sultan of Joló began to pressure Malaysia to return their lands. Something that Malaysia rejected outright.

Invasion of Sabah and start of battle

Everything changed in 2013, when a group of 235 linked to the heirs of the Sultan of Joló invaded Sabah, starting what became known as the Lahad Datu conflictclaiming the sovereignty of the region.

Malaysia responded with military force and stopped the rebels declaring that the state of Sabah was part of the sovereignty of Malaysia. In retaliation, he decided to suspend historic payments to the sultan’s descendants. This suspension marked the beginning of a long international legal dispute since now the heirs did not have the right of ownership of the lands nor did Malaysia recognize the agreement signed in 1878.

Since in 1878 the kingdom of Sabah was under the administrative control of Spain, the sultan’s heirs considered that the historical jurisdiction belonged to Spain and requested arbitration in Spain, trusting that the country’s courts could act as a neutral venue to resolve the conflict between Malaysia and the heirs of the Sultan of Joló.

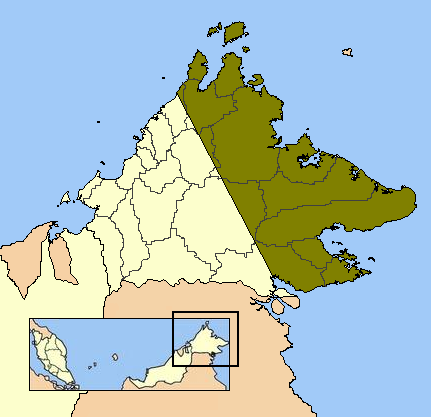

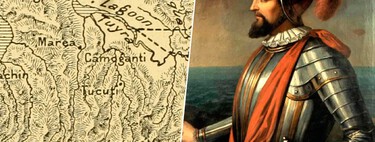

Territory in dispute

From trade disagreement to billion-dollar international conflict

In 2019 and already in Spain, the Superior Court of Justice of Madrid (TSJM) assigned arbitration in principle to lawyer Gonzalo Stampa. However, in 2020 and after studying the case in more detail, the same court ordered arbitrator Stampa to stop the arbitration by determining that the State of Malaysia could not be judged by another State.

Despite the disqualification and orders from the Spanish justice system, Stampa ignored it and continued with the mediation process.

Since it had been banned in Spain, Stampa moved the arbitration to Paris and, in 2022, he dictated a favorable award to the heirs of the sultan. In the award issued by Stampa, which we remember at that time was “free” and no longer recognized by Spain, it could be read: “(…) the Arbitrator decides that the Claimants have the right to recover from the Respondent the restitution value of the rights over the leased territory in northern Borneo. (…) and orders the Respondent to pay the Claimants the sum of 14.92 billion US dollars.”

Painting of the Sultan from the late 19th century

That is to say, not only had he ignored the instructions of the Spanish justice system, but he also condemned Malaysia to pay compensation of 15,000 million dollars to the heirs.

Obviously, nor Malaysia neither Spain nor even Paris Court of Appeal and then the Cour de Cassation French recognized the nullity of the arbitration. In fact, the Supreme Court recently condemned to referee Stampa for contempt and usurpation of functions.

Although no authority recognized this arbitration, the heirs attempted to enforce the award by confiscating Malaysian assets, in the form of Petronas assets, in Holland and Luxembourgbut European courts temporarily stayed the action.

At the same time, the heirs of the Sultan of Joló filed a new complaint against Spain claiming 15.5 billion euros, alleging that the country had hindered the execution of the award. This demand has just been dismissed by the ICSID (International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes) tribunal dependent on the World Bank, which considered that there was no “protected investment” and ordered the heirs to assume the costs of the procedure.

The result is that Spain leaves the dispute without paying a single euro, while the legal battle for territory and compensation against Malaysia remains open and on multiple fronts in Europe and Asia. What began as an agreement between a sultan and some businessmen more than 140 years ago has become a complex international judicial entanglement that has come close to costing us 15.5 billion for nothing.

The legal imbroglio still has no end in sight. Let’s not celebrate it yet.

In Xataka | Philip II’s most meticulous and ambitious plan for the Spanish Empire: conquer China with the help of Japan

Image | Wikimedia Commons (Kawaputra)

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings